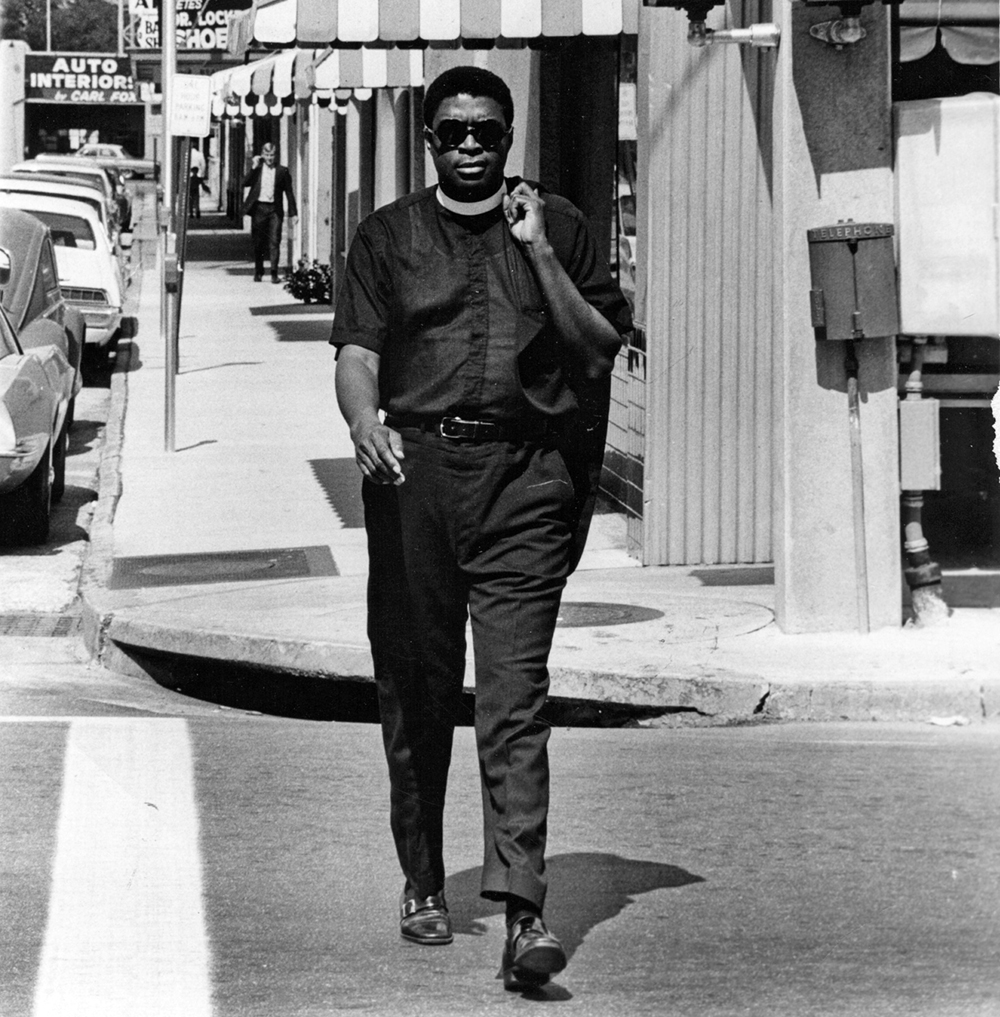

The Rev. Nelson Pinder in Orlando in 1970, courtesy of the Orlando Sentinel.

By Tana Mosier Porter from the Fall 2013 edition of Reflections From Central Florida

The Reverend Canon Nelson Wardell Pinder, doctor of Divinity, graduated from Bethune-Cookman College in 1956 and from Nashotah House Seminary in Wisconsin three years later. He came to Orlando in 1959 to become the rector of the Episcopal Church of Saint John the Baptist, in Orlando’s African American community of Parramore.

When Father Pinder tried to get into a taxi at the Orlando airport, the driver told him the cab carried only whites and that he would have to call another cab because “colored folks and white folks” didn’t mix together. Father Pinder observed that he didn’t want to mix, he just wanted a ride. Turned away again when he tried to buy a cup of coffee, he concluded that Orlando needed to change.

The new rector found in Orlando a rigidly segregated Southern city in which most black residents lived in a separate world on the west side of the railroad tracks. Enforced separation of the races determined where blacks could live, shop, and go to school. The “Jim Crow” system of segregation extended to separate restrooms, drinking fountains, waiting rooms, and entrances to buildings, as well as a myriad of other restrictions.

Before 1955, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, organized in 1909, fought discrimination quietly through court cases and lobbying. After 1955 and events including the brutal murder in Mississippi of Emmett Till, a black fourteen-year-old boy who was visiting from Chicago, the movement turned to civil disobedience. Activist groups such as the Congress of Racial Equality, formed in 1942, and the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee, organized in 1960, worked with black youth, while the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, led by the Rev. Martin Luther King, Jr., began in 1957 to organize churches and clergy in a program of nonviolent protest patterned after the passive resistance of Mohandas Gandhi in India.

A new challenge

Father Pinder brought to Orlando his experience with the civil rights movement in the North, where he had participated in marches, sit-ins, and strikes in Milwaukee, New York, Detroit, and Chicago during the 1950s. In Orlando, he faced a new challenge. City leaders, black and white, feared that racial disturbances would compromise Orlando’s tourist economy, and with it the livelihoods of many African American families. Concerned citizens from both races worked together to end segregation gradually and peacefully.

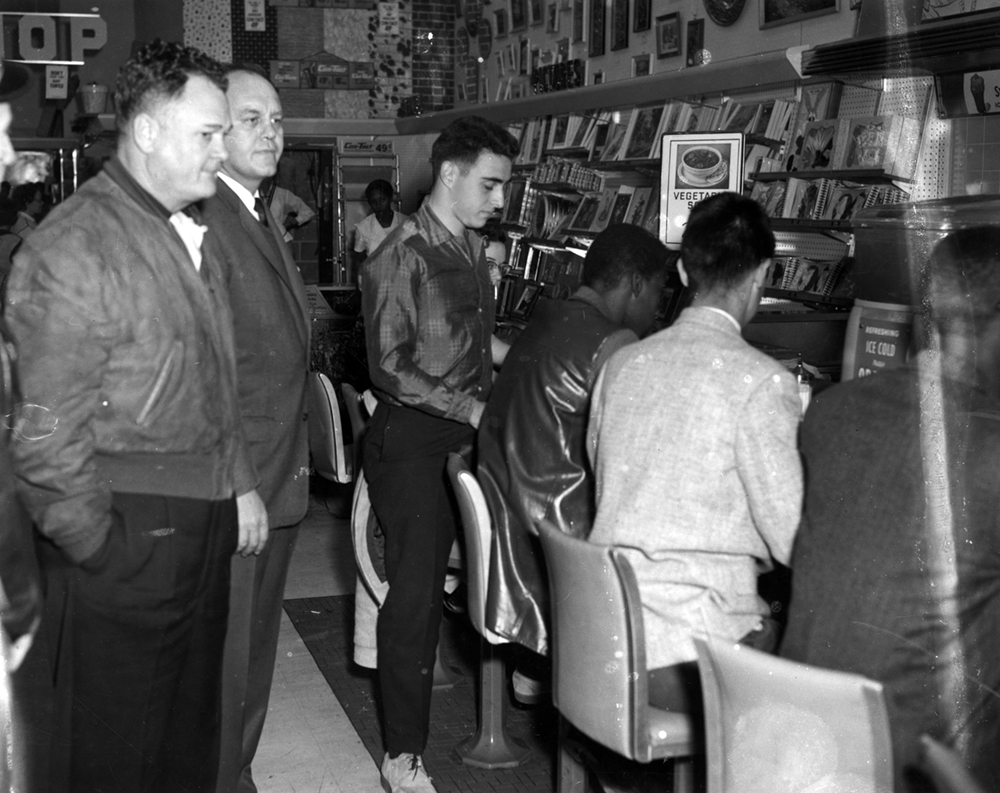

In 1962 Father Pinder helped organize sit-ins to challenge the law against blacks eating while seated at drugstore and dime-store lunch counters. In controlled demonstrations, African American teenagers sat down at the lunch counters and waited to be served. NAACP representatives met with city officials to assure that there would be no violence. The store managers knew about the sit-ins, as did the police, who agreed that as long as the young people sat-in peacefully, they would be allowed to continue. Bail money was arranged in the event that things went wrong.

Father Pinder’s teenage activists belonged to the Liberal Religious Youth group that met at Orlando’s First Unitarian Church, and to a local chapter of the NAACP Youth Council, started in 1959. Most would graduate with the class of 1962 from Jones High School, then Orlando’s segregated school for African Americans. Trained and rehearsed to accept punishment and humiliation without reacting, the students understood that they might be cursed, spat on, slapped, pushed, yelled at, and called names. They knew that if the management played the “Star-Spangled Banner,” they must stand up, even though their stools would be removed from under them, because if they did not stand up, they would be arrested for dishonoring America. They knew fear, but they also knew that they had less to lose than their elders, whose homes and jobs could have been jeopardized by participation in the protests.

In 1960, African Americans conduct a sit-in at a Woolworth’s lunch counter. Orlando’s mainstream media followed a policy of not photographing sit-ins, to allow them to happen peacefully. Image courtesy of the State Archives of Florida.

A difficult path

The students met each day after school and went together to the dime stores and drugstores to sit-in at lunch counters that closed when they appeared. At some counters, workers unscrewed the tops from the stools so that the students could not sit on them. The students waited and then left quietly to try another store.

On March 9, 1962, eleven students in the Jones High School Class of 1962 went to three drugstores. At the first one, workers removed the seats; at the second one, they ignored the protesters. The management at the third store had the teenagers arrested. Bail money, $250 per student, came quickly from the black community, but not before the young people spent a frightening night at the prison farm Orange County then operated on West Colonial Drive.

Some of the same students were later arrested in the ticket line at Orlando’s Beacham Theater when a white segregationist group threatened the young black people who were “standing-in” to buy tickets. The police arrested the African Americans.

The Rev. Canon Nelson Pinder and his wife, Marion. Image courtesy of the Pinder Family.

Change without violence

While the sit-ins, stand-ins, and wade-ins continued, negotiations with Orlando business people began to bring the change Father Pinder had envisioned, and it came without violence. White businesses began to serve blacks, and gradually “whites only” signs came down. Finally, the Civil Rights Act of 1964 outlawed segregation in public places throughout the nation.

Father Pinder led the fight to integrate Orlando’s restaurants and lunch counters, stores, playgrounds, parks, and schools. He helped to persuade the Orlando Sentinel to eliminate its “Negro Section” and to cover African Americans in the main edition of the paper. Three grocery stores that refused to hire blacks closed after he led boycotts against them. The Parramore community knew Father Pinder as the “Street Priest of Orlando,” for his tireless efforts to help street people and troubled youths.

The Episcopal Church ordained Father Pinder in 1960, and he continued his education, earning a graduate degree from Florida Agricultural & Mechanical University in 1974. Bethune-Cookman College awarded him an honorary doctorate of Divinity in 1976, and he taught at Bethune-Cookman and Rollins colleges, and at Stetson University. A regular on boards and advisory councils, he has received innumerable awards and honors. In 2010, the Episcopal Diocese of Central Florida honored him for his 50 years of service.

The students who stood with Father Pinder in 1962 graduated from Jones High School and continued their own educations. Some became lawyers, school teachers, and business owners. They looked back with pride on their own contributions to the civil rights movement in Orlando.

Note: The Rev. Canon Nelson Pinder served Orlando’s Episcopal Church of St. John the Baptist for 52 years and spent decades as a community and civil rights leader. He received many accolades in his later years, including the History Center’s Donald A. Cheney Award in 2015. After Father Pinder’s death on July 10, 2022, at age 89, a spokesperson for the City of Orlando noted: “When recalling the Civil Rights Movement, many think of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. or John Lewis, but here Father Pinder was our peaceful shepherd.”