By Sarah M. Boye, from the Spring 2025 Edition of Reflections from Central Florida

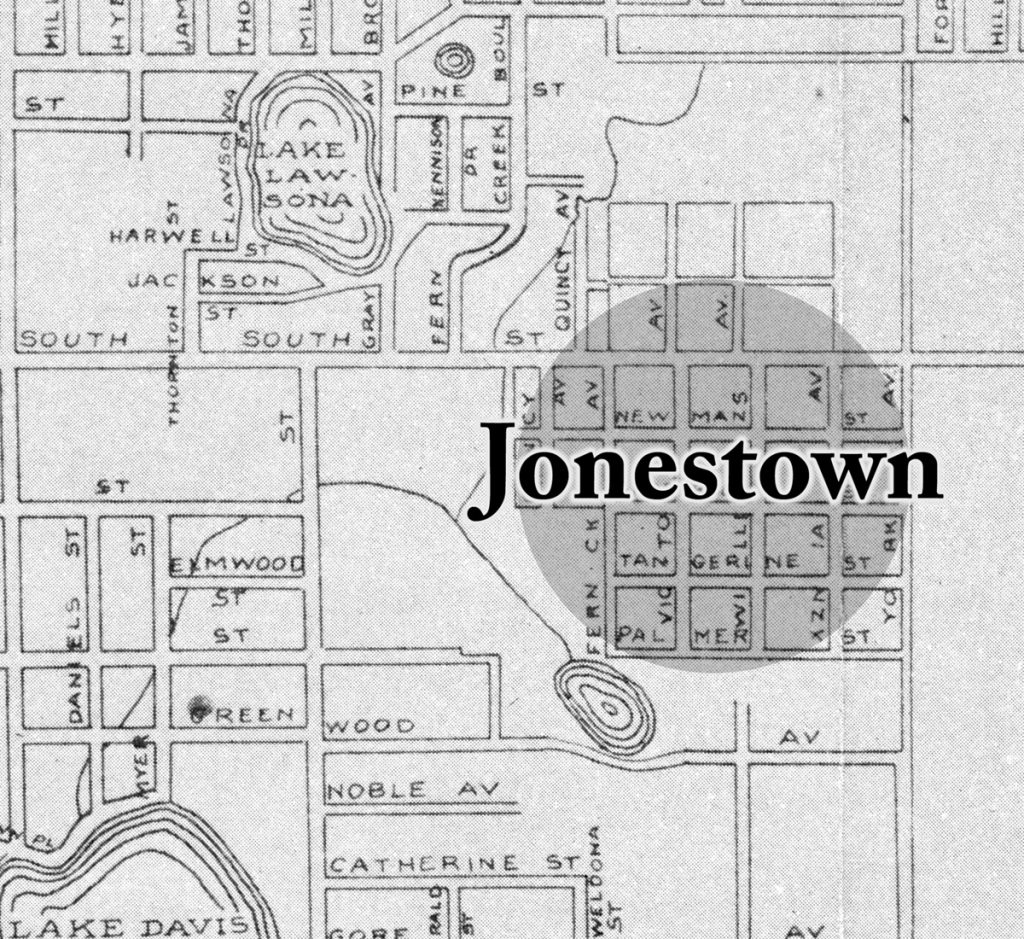

On a breezy fall day, a group of tour attendees stood solemnly by the grave of Osborne Brooks in Orlando’s Greenwood Cemetery, listening as the tour guide explained his family’s connection to the city. Like many Black residents of Orlando born in the early 20th century, Brooks lived in Jonestown, one of three segregated zones of the city. When he was born in 1915, Jonestown was a vibrant neighborhood, full of families who lived and worked in nearby downtown Orlando. Due to the conventions of white supremacy, they were kept on what was then the outskirts of the City Beautiful.

Much like the city itself during the Jim Crow era, Greenwood was also segregated, albeit within the cemetery gates. Black residents were relegated to one of three sections of the cemetery. Osborne Brooks’s grave lies in the northeast corner of section three in Greenwood, next to Isabell Demps, his aunt. His mother, Sophronia Brooks, is buried there in an unmarked grave. Relegated to the outskirts of Orlando in life, and nearly forgotten in death, Brooks and his family are a poignant reminder of Jonestown, Orlando’s first Black neighborhood, and its residents.

Segregated in death

Jonestown was established in the 1880s just outside the city’s southern boundary. As Orlando and Jonestown developed, eight pioneer Orlando residents formed the Orlando Cemetery Company and purchased 40 acres of land south of Jonestown, down the hill and out of sight of the City of Orlando.

Most unusually at the time, the Orlando Cemetery allowed for burials of both white and Black residents within its gates. Black residents were initially relegated to the area farthest from the original entrance on Gore Street, along the west side of section H – marked on an early map as the “Old Colored Cemetery” in a city plat book.

In 1893, one year after the City of Orlando purchased the cemetery from its founders, segregation of those buried there was codified in the first city ordinances that included the new municipal cemetery. As Orlando added more acreage to the cemetery, the segregated sections moved northward to just outside Jonestown’s southern boundary.

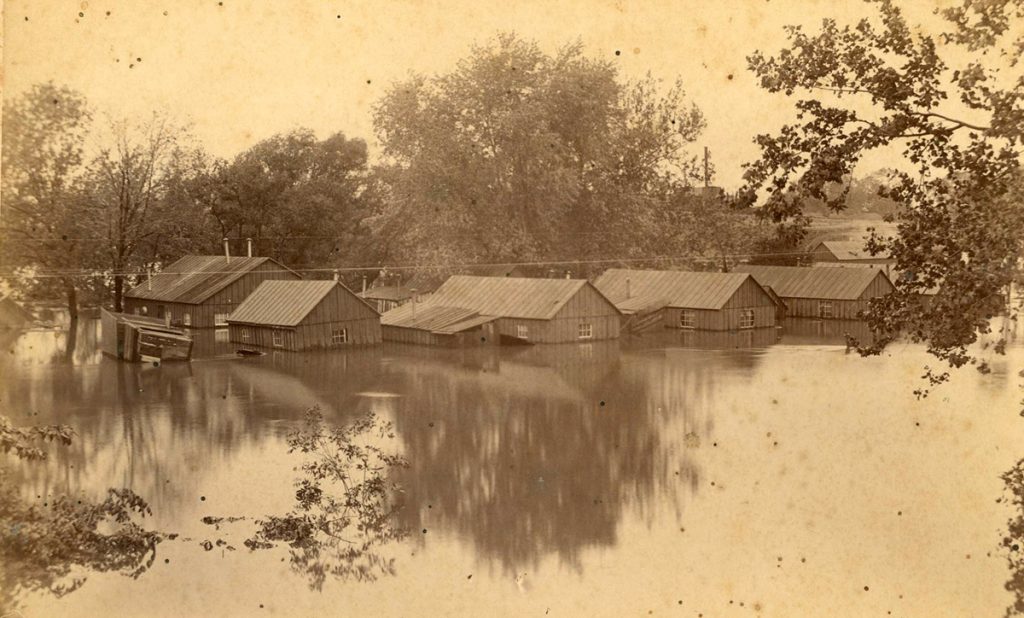

The sinkhole, now known as Lake Greenwood, would regularly flood the community of Jonestown until a drainage system was established. This photo could be from any Jonestown flood between the 1880s and 1904.

Magruder’s influence and the 1915 flood

Many of Jonestown’s early residents worked for James Magruder, a white man who owned numerous business ventures in Orlando, including the Empire Hotel and the Lucerne Theater. By 1890, Magruder had developed a subdivision for his employees that extended from South Street to Palmer Avenue and contained 160 lots. Due to issues with flooding from a nearby sinkhole (now known as Lake Greenwood), residents began moving northward, establishing their own subdivisions, named after Jonestown residents such as the Rev. George Washington Coar or Black heroes such as civil rights icon Frederick Douglass.

Just one month after Osborne Brooks was born, an immense rainfall submerged Jonestown in October 1915. Many of the one-story, tin-roofed homes in Magruder’s subdivision flooded to their rooflines. Magruder lost 20 pigs and hogs on his agricultural properties in Jonestown.

The Orlando Morning Sentinel reported that the pig pen was carried across the newly formed lake but neglected to mention the fate of Jonestown residents affected by the 1915 flood, which wreaked far more havoc than merely washing away animal pens. On November 10, a plague of tiny frogs overtook Jonestown. The Sentinel declared that the frogs, who were “largely in their element in Jonestown,” were “seen in innumerable numbers, piled upon one another, several inches deep.” It was in these unfortunate conditions that Bert and Sophronia Brooks welcomed their son Osborne that November.

The year 1915 brought other local developments, which included changing the name of the cemetery to Greenwood Cemetery to better align with Orlando’s motto, “The City Beautiful.” However, as young Osborne grew up in the wake of such destruction and segregation, the meaning of that motto would be put to the test.

Bert and Sophronia Brooks and their son Osborn lived at 945 E. South Street in 1916.

Life in Jonestown

Young Osborne Brooks likely attended the nearby “Colored School” on Newman Avenue, where he learned to read by the glow of oil lamps, and worshipped at Mount Olive Christian Methodist Episcopal Church on South Street. Both of his parents worked at the South Florida Foundry on West Pine Street and created the ironwork that was used in the construction of Orlando.

Though the Brooks family owned their home in 1920 on East South Street, by the end of the decade they moved several times, suggesting some economic instability. In 1929, when Osborne was just 13 years old, his mother, Sophronia, died of pneumonia and was buried in “strangers’ row” of section K in Greenwood Cemetery. After her death, Osborne’s father, Bert, went to Jacksonville, likely to look for work, and left Osborne in the care of his maternal aunts, Isabell and Bertha.

As he visited his mother’s gravesite in Greenwood Cemetery with his aunts in the weeks following her death, Osborne likely would have heard the familiar strains of “Dixie” played on Confederate Memorial Day. Each April, just down the hill from Sophronia Brooks’s final resting place, the United Daughters of the Confederacy decorated the graves of Civil War soldiers, in proximity to Orlando’s first Black neighborhood.

Growing up, Osborne Brooks undoubtedly encountered the oppression of systemic racism that was the standard of life in Orlando during the early 20th century. Throughout his formative years, the Ku Klux Klan had resurfaced to terrorize Black residents. By 1931, white supremacy was so mainstream that 60 white-robed Klan members marched just outside Jonestown alongside veterans and Scout troops in the Armistice Day parade.

Sadly, within three years of his mother’s death, in 1932, Osborne Brooks was left an orphan when his father died of heart failure. In Jacksonville, Bert Brooks was buried in Lone Star Cemetery – like his wife, in an unmarked grave. Osborne continued his schooling and likely attended Jones High School, the only public high school available to Orlando’s Black students. In 1933 he was among the first few classes of students to graduate from the 12th grade at the segregated high school.

The marker in Greenwood Cemetery for section K, which was originally segregated.

The demise of Jonestown

By 1935, the Magruder family had amassed an enormous tax debt and in exchange transferred their 30-acre subdivision in Jonestown to the City of Orlando. The city promptly used this property to expand Greenwood Cemetery to the north. At the same time, white-owned subdivisions were growing around the once-vibrant Black community. White residents publicly complained about Jonestown’s proximity to their properties and called for the removal of its residents.

Two disasters assisted these belligerent white Orlandoans in their efforts to remove their Black neighbors. First, a fire destroyed a home and killed a man in Jonestown on Nov. 19, 1938, and in February 1939 white residents protested the permit needed for rebuilding. The same month, the Orlando Housing Authority announced plans to remove Jonestown, which the Orlando Morning Sentinel called “a cancer which has long gnawed at the vitals of various city administrations.” Finally, in October 1939, a sinkhole collapsed at the corner of East South and Quincy streets, near the home Osborne Brooks had shared with his aunt Isabell Demps, furthering efforts to condemn nearby properties.

By 1939, Orlando’s segregation zoning ordinances had relegated Black residents to three neighborhoods: Holden, Callahan, and Jonestown. Overcrowding in these areas made relocation difficult for residents, so a low-income housing project, Griffin Park, was built to encourage Jonestown’s residents to leave. The Orlando Housing Authority pushed forward with plans to replace the remaining portions of Jonestown with low-income housing for white residents. In total, 48 homes, Mount Olive CME Church, and a store were condemned as slums and demolished to make way for that housing, named Reeves Terrace, in 1942.

Around this time, just a few short weeks before the attack on Pearl Harbor on Dec. 7, 1941, Osborne Brooks escaped the destruction of his home and enlisted in the United States Army Air Force. He went on to serve in the “Double Victory” campaign that aimed to end fascism worldwide and racism at home during World War II. The U.S. military was segregated during the war, but due to his education, Brooks rose to the rank of sergeant in Squadron C of the 336th Army Air Force Base Unit. As a sergeant he played a crucial role in the smooth operation of his squadron’s missions, combining leadership with technical expertise. His duties would have been an integral contribution to the war effort despite the systemic challenges of segregation. He served through the entire war and was honorably discharged on Oct. 7, 1945.

When he returned from his military service in World War II, Osborne Brooks would see that Jonestown was a shadow of its former self. The all-white Reeves Terrace had grown, but by 1951 only 11 families were still living in Jonestown. Brooks and his aunt Isabell moved to the Holden neighborhood, nearer to the Orlando Drive-In Theater, where he worked as a janitor.

As the years passed, more longtime residents of Jonestown left, until in 1962, Brooks’s one-time neighbor Virginia Spellman died, and the city acquired her property. This prompted the only other remaining Jonestown resident, Mattie Young, to sell her home to the city, officially ending the lifespan of Orlando’s first Black neighborhood.

Three short years later, Osborne Brooks was admitted to the Florida Sanitarium and Hospital, where he died on Nov. 7, 1965, just shy of his 50th birthday. He was buried in section three of Greenwood Cemetery on land that was once Jonestown. Sections three, K, and T remained segregated until a complaint by the NAACP in 1967 repealed the ordinance requiring segregated burials in the cemetery.

Today, Osborne Brooks’s and Jonestown’s place in history are a stop on a walking tour in the cemetery. Recent efforts by historians to commemorate Jonestown and its residents, like Brooks, reflect the desire of the local community to uncover and restore this vital piece of Orlando’s historical consciousness. These initiatives challenge the fulfillment of the “City Beautiful” motto by helping Orlando recognize its painful past. The next time you find yourself in Greenwood Cemetery, stop by Osborne Brooks’s grave, say his name, and remember Jonestown.