By Don Philpott from the Fall 2024 Edition of Reflections Magazine

After a decade-long quest that began with a hidden grave marker, the volunteer Wekiva Wilderness Trust is bringing to light the story of a lost town near Rock Springs.

Ethel is one of Florida’s many forgotten communities that once flourished and then disappeared in the mists of time – a post-Civil War township in what is now Rock Springs Run State Reserve, a 14,000-acre park in Sorrento, bordering Lake, Orange, and Seminole counties. Now, after more than a decade of research, Ethel and its townsfolk have been brought back to life.

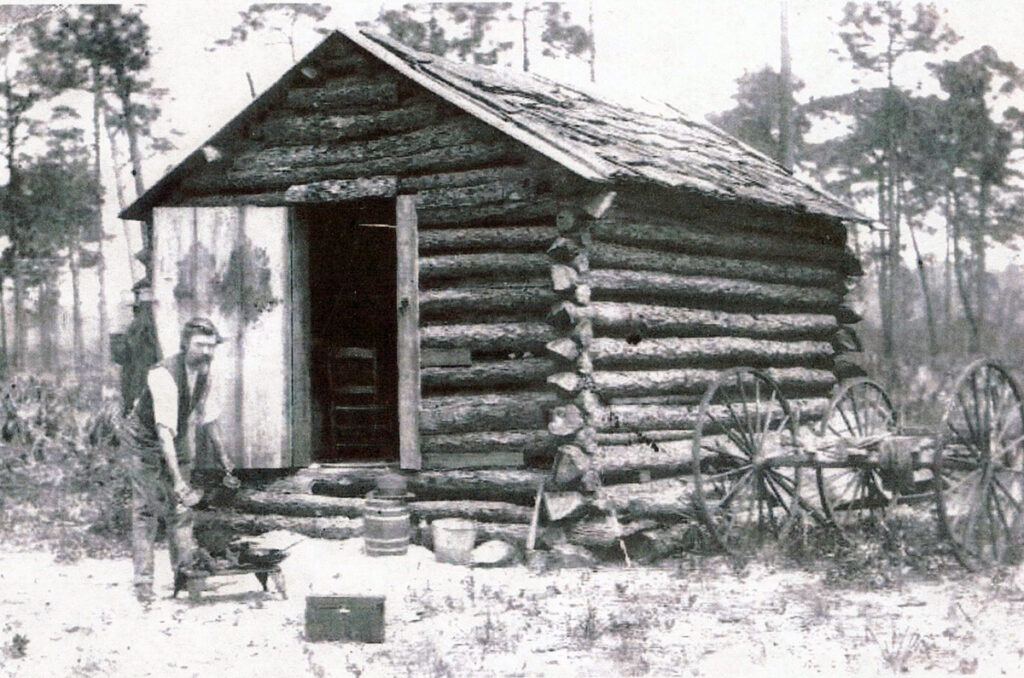

A photo from the late 1900s shows Ethel resident Finley B. Clark outside his cabin. Courtesy Virginia Buras.

The path to discovery

Almost nothing was known about Ethel until Tony Moore, a park volunteer and retired land surveyor, spotted something almost hidden in chest-high grass at the edge of woodland. Imagine his surprise when he saw that it was a tombstone inscribed with the name Luke Moore, the same last name as his. A few yards away, he discovered a second tombstone, also with the last name of Moore. This marked the graves of William and Charlotte Moore, who were likely the first settlers in Ethel.

Intrigued by this remarkable coincidence, Tony Moore began research to see if he was related to Luke, William, or Charlotte. Although ultimately he found no connection, his quest led him instead to Ethel. Efforts to know more continued after his death in 2012 and today give us a fascinating insight into Ethel and the people who lived there.

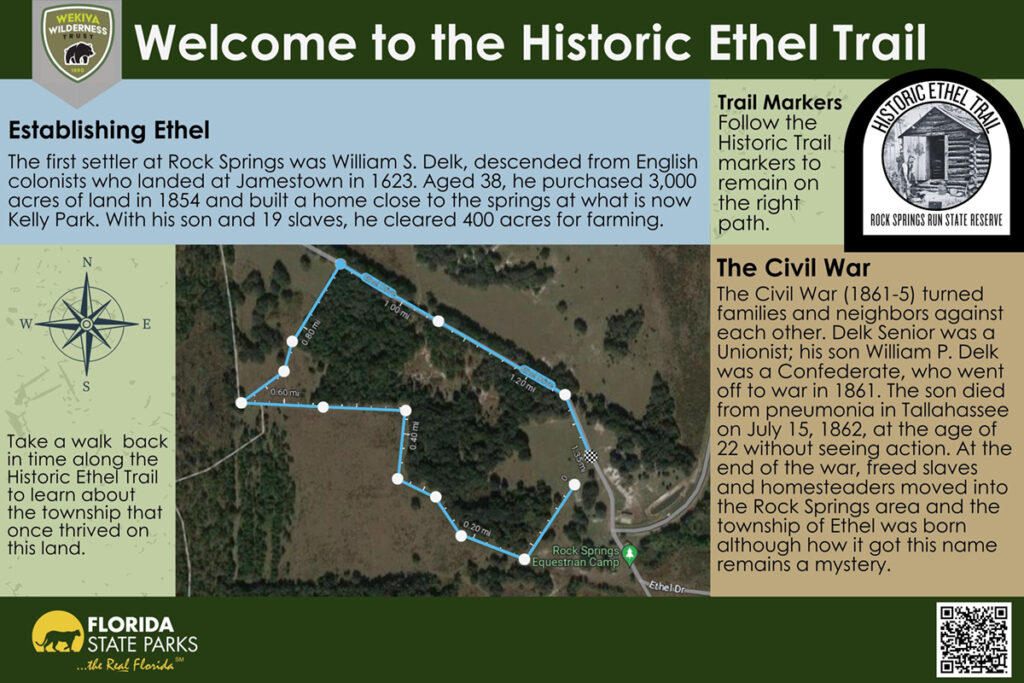

We know that in 1854, William Delk, whose forefathers came to America aboard the Mayflower, had a 3,000-acre plantation at what is now Kelly Park. He farmed 400 acres with his son, two indentured white laborers, and 19 enslaved Black people, growing cotton, rice, sugar cane, and corn.

During the Civil War, Delk supported the Union and refused to buy Confederate bonds, which led to his arrest. He managed to escape and returned to his plantation, where he freed the enslaved workers, and then made his way to Jacksonville to offer his services to the Union Army. He spent the rest of the war rounding up cattle that he sold to the Army but was constantly in trouble because he was not too picky about where he got the animals so long as he was paid.

The enslaved people freed by Delk included Joseph Robards, Delk’s illegitimate son, and his half-brother Anthony Frazier (they shared the same mother), both of whom traveled to St. Augustine and enlisted in the Union Army.

After the war, Delk returned to Rock Springs and reclaimed his property, while Robards and Frazier, now free men, bought their own land nearby with the $100 bounty they received for their military service. Soon, the Moores and other families moved to the area, having acquired their 160 acres of free land under the 1862 Homestead Act, and the township of Ethel was born.

Finley B. and Margaret Click in front of their Ethel cabin. This style of cabin was often called a “dogtrot” house because of the breezeway that ran through the building. Courtesy Virginia Buras.

Homesteading at Ethel

Homesteaders were required to clear the land, build a home, and farm the land for five years. They also had to stake their claim by paying an $18 filing fee. This was a large sum of money for most folks, and the nearest filing office in Sanford (formerly Mellonville) was a day’s journey away by ox cart and then another day to return home. As a result, many claims were never filed until either the land was sold or the landowner died and proof of the filing was needed for probate. Delk’s land deed was not filed until after his death in 1885.

William and Charlotte Moore arrived in Ethel in the late 1860s with their three sons. Alonzo, aged 30, Angus, 48, and Newton, 24. The two eldest boys soon returned to South Carolina, but William, Charlotte, and Newton spent the rest of their lives in Ethel and were buried in Ethel Cemetery, a one-acre site donated by William.

From searching land deed records we now know almost all the families who lived at Ethel and where their homesteads were. We have been able to trace many of their descendants who generously loaned old family albums, letters, postcards, and other documents that describe what everyday life was like in Ethel. It is these contemporary accounts that have brought Ethel to life again.

Finley Belshazzar Click arrived in Ethel around 1887, leaving his wife Margaret and children in North Carolina until he had established himself. While he was building his cabin, he slept in a makeshift A-frame shelter made from branches with palm-frond thatching. In one letter, he complained to his wife that it was sometimes difficult to sleep at night because of the snakes slithering through the thatching. Apart from building the cabin, he had to clear more land, plant crops, and cultivate them. It was eight years before the family was reunited, although he did take the train to visit them on at least two occasions.

Click’s first log cabin was 16 feet square with about 500 hand-carved cedar shingles. He and his wife and three sons lived in it for almost 15 years. In 1910, he built a larger cabin with two rooms separated by a breezeway and used the first cabin as a storehouse.

Like most settlers, he fashioned his own furniture from wood – beds, tables, and chairs. He braided natural materials to make rope, grew what crops he could, and foraged, hunted, and fished to put food on the table. His wife would get up at 4 a.m. to cook the food for the day in an outside kitchen. Later, larger cabins did have brick chimneys to vent an open fire or wood burning stove. All the food was prepared at the same time, as it was too hot during the day to cook over a roaring fire and, besides, there were many other chores to do.

After it was cooked, the food would be put on a table covered with a tablecloth. After breakfast, the four corners of the cloth would be gathered up and knotted to protect the food from insects. Lunch, the main meal of the day, and supper were usually eaten cold.

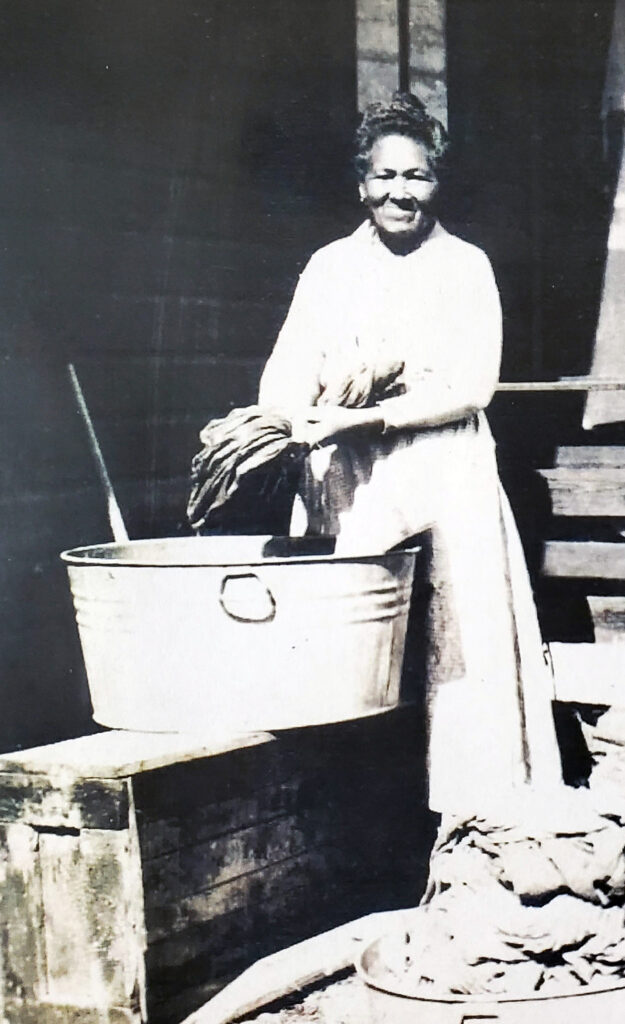

Mary Frazier with a wash tub. Courtesy East Lake Historical Society.

A growing community

By 1888, Ethel had a post office, store, railway station, and one-room school. The school also doubled as a church, where services were conducted every other Sunday by a preacher who traveled from Enterprise by horse and buggy and then used the ferry at Wekiva to get to Ethel. Wekiva was a small settlement on the river about a mile east of Ethel. Wekiwa Springs at that time was known as Clay Springs.

The school at Ethel served white children only from Ethel and Wekiva. The teacher was a young, single woman who taught all grades together, although attendance was poor. It was not compulsory to go to school, and chores at home took precedence.

The school year consisted of one term of three consecutive months with the teacher choosing which months to teach. She was paid $1 per student per month.

In 1917, the schoolteacher was 18-year-old Theresa Dawson. In 1918, she married Edward von Herbulis, who built the first two-story house in Ethel. She continued to teach and in her spare time made citrus marmalades and various flavored jellies that she gave to neighbors. Her products were so popular that the family moved to Mount Plymouth, about 5 miles away, and started a jelly factory – The Lake County Preserving Company. Its products were sold to grocers throughout Florida as well as out-of-state customers.

Unfortunately, the couple’s story did not have a happy ending. On June 13, 1968, an intruder broke into their home and stabbed each of them multiple times. Edward died but Theresa, although critically wounded, survived. The Mount Dora Topic, the local newspaper, said at the time that authorities believed the attack was premeditated. The intruder was never caught, and the unsolved murder remains the oldest Lake County cold case.

Anthony Frazier, freed by Delk from enslavement, bought and sold many parcels of land in and around Ethel for 50 years and became a respected member of the community. His wife, Mary, whom he met while his Black infantry unit occupied Charleston, S.C., in 1865, was the local midwife and delivered many of the babies born in Ethel. Frazier’s most remarkable achievement took place in 1880, when he was appointed Orange County’s special commissioner of roads.

An interpretive marker for the Historic Ethel Trail at Rock Springs Run State Reserve.

Telling the story

In the 1920s people started to drift away to move to surrounding towns that offered more job opportunities and better facilities, and Ethel started to slowly fade away. Had it not been for that chance discovery of the two headstones, the story of Ethel would never have been told – and now it can.

The Wekiva Wilderness Trust, the volunteer, nonprofit organization that supports the work of the Wekiva River Basin State Parks, which includes Rock Springs, has launched the Ethel Project. The Historic Ethel Trail has been opened. It is a wheelchair-accessible 1.5-mile loop that takes visitors around what was the heart of Ethel. Interpretive signs along the route explain the history of Ethel and what life was like back then. There are guided walks twice a month, and a self-guided-tour brochure is available at the trailhead for those who want to explore by themselves. A free ebook about the history of Ethel can be downloaded from the trust’s website at www.wwt-cso.com.

Two cabins are being built, exact replicas of the first Click family cabin. The first will be a small museum, and the other will be sparsely furnished, as it would have been. The Wekiva Wilderness Trust is raising funds to add to them by creating Ethel Village, with more cabins, the store and schoolhouse, and kitchen gardens. Each building will show a different aspect of life back then. We have invited all the schools in our tri-county area (Orange, Seminole, and Lake) to visit Ethel and learn about this fascinating slice of local history.

Footnote: Luke Moore, whose tombstone started the quest that rediscovered Ethel, had no link with the town other than being found dead on a train that stopped at Ethel station in 1914. The good people of Ethel buried him in a simple grave. It took seven years before his family discovered what had happened to him, and they had the elaborate headstone installed – but that is another story!

About the author: Don Philpott has over 50 years of experience as an award-winning writer, journalist, amateur historian, and passionate campaigner for conservation and the environment. Now a full-time writer and volunteer, he has more than 250 books published on a wide range of subjects.