By Joy Wallace Dickinson from the Fall 2023 edition of Reflections Magazine

In 1954, the influential Orlandoan poured his love of words, his sharp wit, and his strong opinions into a newspaper column with a mysterious byline inspired by the city’s beloved swans.

Howard Phillips’s college career was not what you’d expect for a fruit grower from Orlando, he recalled decades later. As the elder son of Florida citrus legend Dr. Philip Phillips, he had been expected to follow in his father’s footsteps. But in 1923, as graduation neared, he had not been sure about that – not sure at all. In his years in Cambridge, Massachusetts, far from his hometown, he had immersed himself in English literature, worked hard on the drama club, and met luminaries such as the playwright Eugene O’Neill. He even considered a job at the Theatre Guild in New York. But in the end, Phillips did return to Orlando, where in the 1920s he started on a path that would make him his father’s successor in business and philanthropy.

From today’s perspective, he made an impact on his hometown that few Orlandoans could equal. Dr. Phillips Charities, his family’s philanthropic legacy, has invested more than $220 million in the community, its website notes, and Howard Phillips’s historic role has been recognized as vital. When he donated his family’s home on Lake Lucerne to the city in the 1970s, it helped inspire Orlando’s early historic preservation movement. His own house on Lake Formosa was ultimately transformed into Orlando’s Mennello Museum of Art.

He left other legacies, too. The oral-history interviews Phillips recorded in 1975 brim with details about Orlando in the early 20th century, when his father, whom folks called Doc, and his mother, Della, hosted music recitals in their grand home. (You can hear his reflections, in his own voice, at OrlandoMemory.com.) But years before that, he created a more hidden gift for the future. In 1954, Howard Phillips secretly wrote for the Orlando Sentinel more than 50 columns under the pen name “Cyg Cob.” In thousands of typeset words, he revealed much about his community and about himself – a man whose life, like the column, was at once quite public and deeply private.

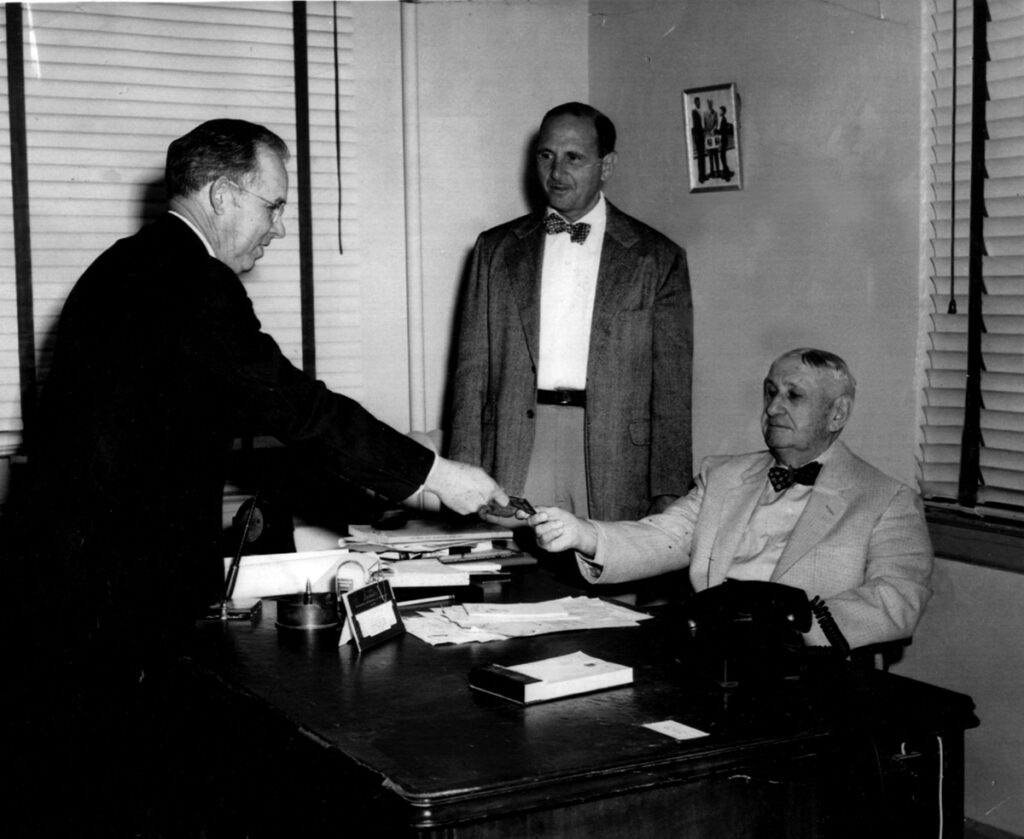

Howard Phillips (center) and his father, Dr. Philip Phillips (right), were photographed together in 1956, a couple of years after Howard Phillips’s secret work on the Orlando Sentinel’s “Cyg Cob Says” column. The man at left is not identified in notes with the photo, which was perhaps related to the two Phillipses’ establishment of the Committee of One Hundred of Orange County, a nonprofit aimed to aid the families of law enforcement officers and firefighters who were killed in the line of duty. Born in 1874, Dr. Phillips died in 1959.

A life in the spotlight

The Phillips family “became as famous for what wasn’t known about them as for what was,” a Sentinel feature noted in 1987. “They drew the line at becoming anything approaching a public presence in the city.” But that was never strictly true of Howard Phillips. From his youth, his name had appeared in Orlando’s newspapers. From his rose-decorated 16th birthday party to his dancing skills in a musical revue – he “could move his feet to music as well as any professional,” the writer effused – he had grown up in the city’s spotlight, when everybody knew his name. His 1918 Orlando High School graduation even took place in the Phillips Theatre, which his father opened in 1917.

As he joined the family business, his name continued in the news. In the 1920s into the ’40s, social items noted Howard Phillips’s travels, “looking after his father’s large citrus interests,” and reported on his guests, including the English author Cecil Roberts, who dedicated a novel to him. Articles detailed his 1928 lecture on drama to the Sorosis Woman’s Club, his thoughts on subjects ranging from the game of bridge to the marketing of tangerines, and his military service in World War II. He joined the U.S. Army as a captain at Orlando Army Air Base in late March 1942, when he had just turned 40, and served as a supply officer for 18 months in Europe, returning in September 1945 as a lieutenant colonel.

By the 1950s, Howard Phillips had long experienced his movements being reported in his hometown in a newsprint parade a little like an antique version of today’s Instagram feed. Beginning on Feb. 16, 1954, he turned the tables and became the one doing the writing, offering a singular public view into his private thoughts and opinions through a new Sentinel column, “Cyg Cob Says.” The author was a “native Orlandoan” whose true identity was a secret, an editorial note explained.

Howard Phillips’s mother, Della (above) accompanied him on piano at violin recitals during his Orlando childhood.

Column with a light touch

In that first column, Cyg Cob set the stage for his fictional persona as he related being summoned to see The Man, his nickname for the paper’s publisher, Martin Andersen. Through a cloud of cigar smoke, The Man lays out his vision for the new column – something with a light touch, “something about the old timers and the new timers, . . . nothing about the two timers, though. . . . Keep it interesting and amusing. Get people talking about it.”

Avoid “fancy words” and big ideas about politics, The Man tells Cyg. Instead, emulate the columns by Billy Rose in New York or Herb Caen in San Francisco – the kind often called three-dot journalism, because they contained varied items, strung together by ellipses, in a pastiche of gossip, witticisms, jibes at neighboring communities, and as many local names as the columnist could muster. Those names offered a vital way to connect with readers during a time when syndicated material was increasing in newspapers across America.

Swanning around

Some readers cheered the new column right away. “Whoever this fellow is, he sure knows how to write in a breezy, humorous and interesting manner,” one letter to the editor declared.

Writing as Cyg Cob, Phillips also supplied those valued local names in sketches of venerable families and notes on entertainment news, but over the weeks, he also served up meaty opinions about topics ranging from citrus concentrate to the value of loyalty in human affairs.

It was an ambitious undertaking, hung on the fictional framework of 1950s-style domestic comedy. Cyg worries about money, wrangles with his wife as she cooks up schemes with the hifalutin Lady-Next-Door, and contends with a supposedly wealthy bachelor relative, Uncle Billy Swann – a sly reference to Orlando’s most famous bird.

Known as the “Tyrant of Lake Lucerne” (Howard Phillips’s home territory), the real Billy the Swan died in the 1930s but gained immortality in Orlando lore through his habit of terrorizing other swans and schoolchildren. He’s still with us, as a work of taxidermy in a glass case in the History Center’s collection.

The name “Cyg Cob” was also swan-inspired. A cob is a male swan, and “Cyg” was short for cygnet, the name for a young swan. Not long after the column began, a little drawing of two swans appeared with it – the work of cartoonist Lynn “Pappy” Brudon. “We presume the bigger swan is Uncle Billy . . . or perhaps the author, Cyg Cob, himself,” an editorial note explained.

But the fictional Cob family were clearly not birds but people, who went to restaurants, dances, and movies. Their names were the kind of intentional silliness that set “Cyg Cob Says” apart from other Sentinel columns. They were part of “Our Town,” as Cyg Cob called his city, and provided the kind of inside joke that might make Orlando readers smile.

Serious opinions, big words

Writing as Cyg, Howard Phillips expressed serious opinions as well as swan silliness. He wasn’t crazy about architect Richard Boone Rogers’s design for Orlando’s new city hall, for example (the one demolished in 1991, as shown in the movie Lethal Weapon 3),

even though Phillips admired other modern buildings. His 1947 home at Daytona Beach Shores, called Wind Drift, looks more like a product of the Bauhaus than a beach cottage – although his friends called it that – and his 1971 house on Lake Formosa that would become the Mennello Museum also featured modern lines.

When it came to music, Cyg Cob expressed eclectic tastes. If you needed salve “for your troubled soul,” he advised readers, buy Marian Anderson’s album Songs of Shubert. He was a big fan of the Peruvian vocalist Yma Sumac but perhaps not so much of revered composer J.S. Bach, whom he said “sometimes bores his listeners.”

In expressing such opinions, Phillips-as-Cyg gleefully ignored his instructions to avoid fancy words. He once described the phrase “The Good Old Days” as a “paralyzing panegyric.” He had also been told not to grind any axes, but he was used to speaking his mind. “I am not known for my mildness,” he once said years later, and he sure wasn’t mild when he wrote that Orlando’s Jaycees had lost their “oomph” and ability to think big. In a rebuking letter to the editor, the club’s president, Andy Serros, called Cyg Cob “grossly uniformed.” Orlando Evening Star columnist Hanley Pogue also took Cob to task, touting the good works of the group’s “young businessmen.”

Phillips even turned his wit toward himself a couple of times. “Howard Phillips is considered a hard-working, hard-driving [regular Simon Legree], hard-playing old bachelor,” his alter ego Cyg Cob wrote. “He pretends to be younger, on the dance floor for instance, than he really is.” Howard Phillips was “something of a mystery,” Cyg noted in another column.

Grace Warlow Barr, Orlando Sentinel food editor, called her friend Howard Phillips “the town’s No. 1 gourmet” in a 1968 feature.

“Man about the globe”

After a prolific six months, “Cyg Cob Says” came to an end in July 1954. Perhaps it turned out to be more work than Phillips could manage and maintain his business duties, which involved shepherding the sale of the Dr. Phillips grove holdings to the Minute Maid Corp. later that year. Or perhaps he wanted to spend the rest of the summer in San Francisco, which he had visited for years on business and for its legendary opera season. Soon, his name turned up in the society pages there. A 1957 item described him as “that attractive man about the globe whose home base is Orlando, Fla.” In 1959, his “annual opera visit” was noted along with his stay in an apartment in the toney Russian Hill area.

And if Phillips’s column was over, he continued to be a presence in Orlando’s papers as the years rolled on. In 1956, a profile by Sentinel veteran Henry Balch deemed him “Orlando’s most eligible bachelor, if he didn’t seem impossible to catch” – a statement perhaps more true than Balch understood. In 1968, Phillips’s good friend Grace Barr, the Sentinel’s food editor, hailed him as “the town’s No. 1 gourmet” and offered his advice on salad dressing, and in 1971, as he approached his 70s, he made news by opening his new home for tours to benefit the Central Florida Museum and Planetarium in Loch Haven Park.

Howard Phillips was a millionaire, after all, in the years when that meant something, and his real life was a far cry from that of the fictional Cyg Cob, who fretted about money and pleasing his boss. After such a life, one might expect to find a gravestone for Howard Phillips among the Orlando pioneers in Greenwood Cemetery or in the Dr. Phillips Cemetery, where his parents are buried. But when he died in San Francisco in September 1979 at the age of 77, his ashes were scattered from a plane over San Francisco Bay, according to his wishes. His death remains painful to write about, even decades later and for those of us who can know him only through the words he left behind. The San Francisco Examiner reported it under the headline “Millionaire identified as murder victim.” The police described the 27-year-old man later convicted in Phillips’s death as a “drifter” known for preying on gay men.

In Orlando, friends and associates reacted with grief and tributes. Grace Barr wept and described her friend’s love of art and literature and the “wonderful warmth” he displayed for “every phase of life.” Martin Andersen, “The Man” in Cyg Cob’s world, described the “countless” good works that Phillips had insisted be kept out of Orlando’s newspapers over the years. And Jean Yothers revealed that Phillips had been the man behind Cyg Cob a quarter-century earlier – something even his closest associates didn’t know.

Perhaps his secret column was one of the ways Howard Phillips maintained a life that was both public and private – a life that didn’t fit the mid-20th-century image of what a business tycoon was supposed to be. For a brief time in the middle of the 1950s, Cyg Cob gave him one way to express his intellect, his creativity, his humor, and his views about the world.

He was at once the globe-trotting sophisticate and the son of “Our Town” who had grown up with Orlando and believed in its future. “I can get features for my column from my fly-specked memory of yesteryear,” he wrote as Cyg Cob, “but tomorrow, to my mind, is the time that really counts.”