A group of women at the Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp pose in Native American garb, circa 1900. Courtesy Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp.

By Adam M. Ware, Ph.D. from the Fall 2015 edition of Reflections From Central Florida

There is no cemetery in Cassadaga, Florida. Perhaps this is not strange.

Begun in the late 19th century, Cassadaga is a small, unincorporated community in Volusia County. Perhaps those who died within its confines are buried in the Northern communities from which they emigrated long ago. Perhaps they are buried in cemeteries nearby – in DeLand, Orange City, or neighboring Lake Helen, home to the cemetery sometimes mistakenly identified as Cassadaga’s.

It would be fair to say, though, that while the burial plots of the deceased are not here in Cassadaga, the dead are indeed around. This is not merely a natural observation: It distills a central tenet of the religious tradition known as spiritualism, a tradition that defines Cassadaga’s unique place as “the Psychic Capital of the World.” How did the community get that way? How did an otherwise undeveloped wilderness become home to the oldest congregation of spiritualists in the South?

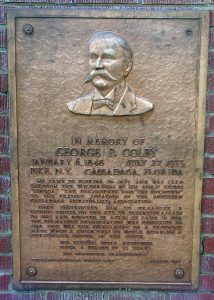

A plaque honoring Cassadaga founder George Colby.

THE VEIL BETWEEN WORLDS

By the time Cassadaga’s founder, George P. Colby, arrived in Florida in 1875, his commitment to spiritualist thinking was well known among seekers up and down the East Coast and especially in New York state, where Colby was born in 1848. He claimed to have had spiritualist inclinations instilled in him at a formative age.

A baptism in freezing lake water, he said, had thinned the veil between our world and the world into which spirits ascend, allowing him direct contact with those on the other side.

Strange or unconventional though it may sound, Colby’s belief in contact with the dead was not an uncommon sentiment in his time. The 19th century was a time of rapid expansion, experimentation, and innovation in the practice of American religious life. Many new religious movements emerged, especially at points of contact between religious thinking and the new natural philosophies inspired by the “scientific revolution” as blends of natural science and supernatural theology. Spiritualism was one such movement. Mormonism and Seventh-day Adventist Christianity are two other American traditions that emerged from the same intellectual climate.

In the minds of Colby and other 19th-century spiritualists, their perception of reality was regular, rational, and scientific, classifying and organizing observations about the natural world. It is in this term, “the natural world,” that spiritualist thinking differs both from most of Christianity and from the natural sciences. Whereas many Christians maintain a belief in a physical resurrection of the body, spiritualists maintain a belief that personalities, not bodies, survive death. Though the varieties of spiritualism are many, these traditions often suggest that the realm inhabited by spirits is an epistemically advantageous space.

Put more simply, spiritualists believe that human personalities survive death intact, and that they are capable of revealing to humanity things we do not yet understand about our own condition and the nature of the universe.

This understanding of the universe reveals the significance of the central practice of spiritualism: the use of mediumship to interpret and communicate, for the living, information provided through contact with the spirit world. George Colby claimed this quality of mediumship had been visited upon him through his frigid baptism, and he spent the better part of his young manhood lecturing on the new realities available to those who might subscribe to spiritualist thinking. Colby acted both as an intellectual apologist, lecturing on behalf of the benefits of séances, and as a medium himself, demonstrating the gifts of séances by performing them.

It was during one such séance, Colby said, that one of his spirit guides, an indigenous American he called Seneca, described to him a parcel of land on which Colby should build a spiritualist retreat. Evidence about the context of this revelation is scarce. Some accounts suggest that the critical communication occurred at the home of T.D. Giddings in Eau Claire, Wis., while others suggest it happened when Colby was touring Iowa. Wherever the genesis of Seneca’s message, Colby and his family heeded the suggestion and headed south later that year.

In October 1875, the Colbys arrived in Jacksonville by train and took a boat south, up the St. Johns River to Blue Springs Landing. The family then traveled by foot through the dense scrub until they arrived at the location Seneca had described, on the shores of what is now Lake Colby. There the Colby family established a homestead of nearly a hundred acres. Before long, the unnamed settlement began accepting visitors from climes more typically associated with spiritualism, including the Cassadaga Free Lakes Association of Cassadaga, N.Y., near Lily Dale.

Postcard of the entrance of Camp Cassadaga – Lake Helen, Florida. From the State Archives of Florida.

ROOTS IN NEW YORK

Like many of the new movements in 19th-century American religious life, spiritualism emerged from the state of New York, and to many practicing spiritualists, the prospect of spending winters in the relatively tropical climes of Florida proved immediately attractive. Nineteen years after Colby discovered the land promised him by Seneca and “a congress of spirits,” the Southern Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp Meeting Association was formed in December 1894. Not a camp in the conventional, outdoorsy sense, Cassadaga is a camp meeting in the historic religious sense. The term “camp meeting” refers to religious events, typically hosted by Holiness ministers, that became common in the early decades of American life.

From the Colbys’ initial homestead and the formation of the Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp 19 years later, Cassadaga grew into an international destination for devotees of spiritualist thought and practice. In 1922, camp leaders built the Cassadaga Hotel to accommodate the tiny community’s growing list of visitors. Indeed, the decade of the 1920s was perhaps the most bustling time in Cassadaga’s history.

It was also the period when Cassadaga began attracting the confusion, suspicion, and interest of locals in nearby communities, many of whom practiced forms of Christianity descended from revival and Holiness traditions. Ministers sometimes warned parishioners of the strange power of Cassadaga and the ritual specialists working there as mediums, insinuating that the mediums’ power derived from darkness and not from “infinite intelligence,” a term spiritualists sometimes use to refer to God.

In the years since Cassadaga’s 1920s boom, the Cassadaga Spiritualist Camp persisted as a mainstay of spiritualist life and practice, though the community has aged significantly. In the year of Colby’s death, 1933, the camp association sold the Cassadaga Hotel, which still operates today, advertising a kind of general supernatural appeal to its visitors. Other forms of supernaturalism have sprung up in the vicinity, promising all manner of divination (i.e., fortune-telling) services such as palmistry.

While compelling for some, it should be noted that these sorts of practices do not necessarily reflect the outlook of spiritualists. Far from being a vague catch-all for the endless variety of “new age” ideas, the belief system of spiritualism—with the medium and the séance at its center—maintains an outlook on the world distinguished chiefly by the possibility, and the moral-intellectual benefit, of regularly communicating with spirits.

Rumors still circulate about the whereabouts of George Colby, who died in June 1933. After his death, his body was interred in nearby Lake Helen, but since then, stories have abounded that his grave there might be empty or that perhaps he is interred in New Smyrna.

After all, although there is no cemetery in Cassadaga, the spirits of the departed are never far away.