Bob Snow talks Dixieland, Skywriting, and How He Changed Orlando

Everything in Bob Snow’s house celebrates another age. Oil paintings in enormous gilt frames line the walls. A spectacular staircase fills the foyer, and an antique grandfather clock chimes the hour. Ancient oaks and fragrant magnolia trees surround the historic Orlando home, which looks like it belongs in Southern Living.

I’ve come here with architectural historian Christine Madrid French and the History Center’s Whitney Broadaway to learn more about how one man inspired the resurrection of Orlando’s downtown at a time when an exodus to shopping malls and suburbs had sucked the life from the urban core of the City Beautiful.

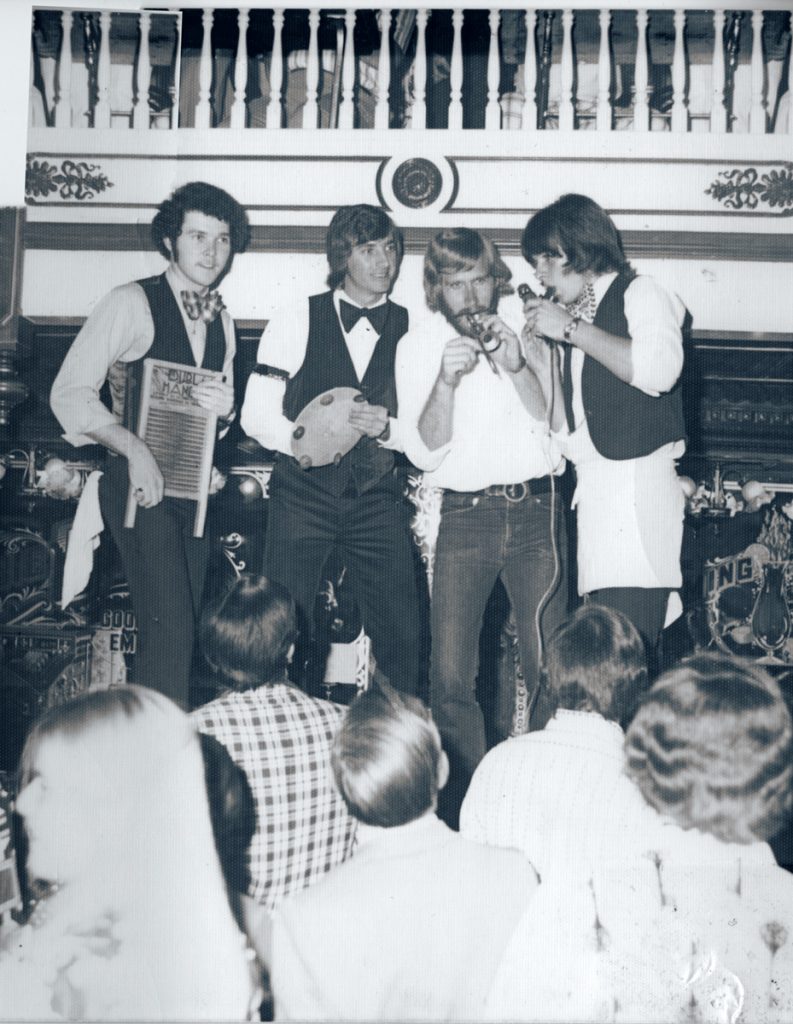

As a former member of the Good Time Gang – the nickname once given to employees of Church Street Station – I’m familiar with many larger-than-life stories about the origins of Rosie O’Grady’s in Orlando and about its founder. We’ve come to talk with him about Church Street Station’s beginnings, as part of our quest to examine the events that shaped Central Florida in the 1970s.

“I love Dixieland jazz”

“It’s amazing how things work out when you don’t have any money,” Snow recalls.

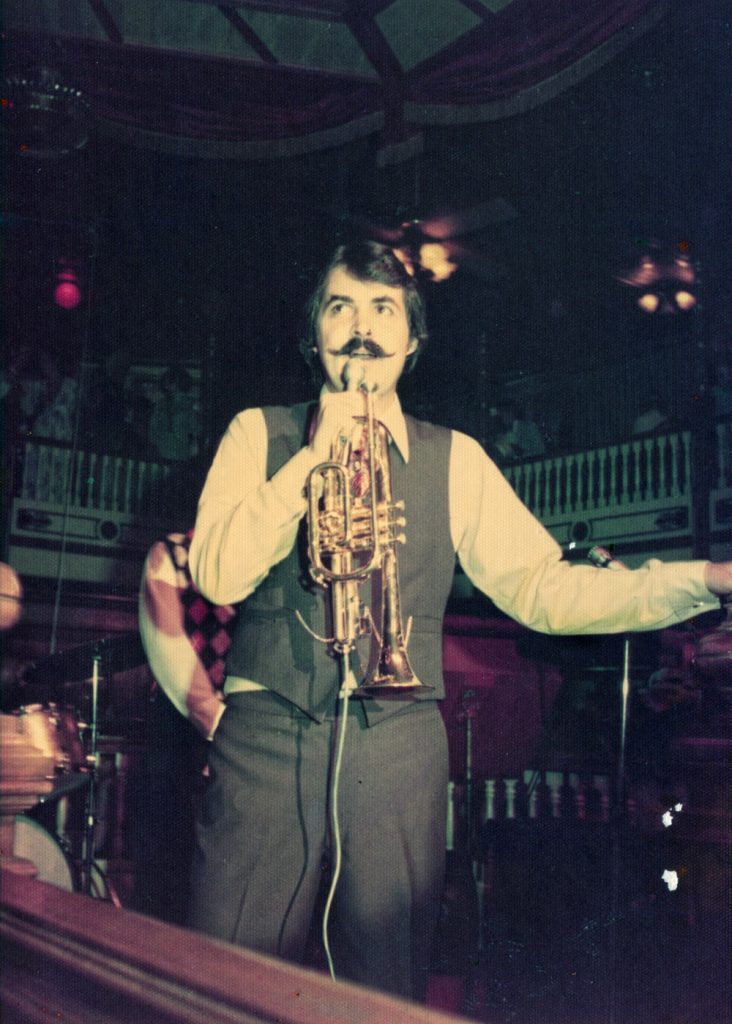

He started his first Rosie O’Grady’s in Pensacola in 1967 with the proceeds from the sale of his Porsche roadster and his last pilot’s paycheck from the U.S. Navy. He moonlighted as a professional Dixieland trumpet player and recruited eight of the “best Dixieland players in the world” to move to Pensacola to create the music that fuelled the high-energy “Good Time Emporium.”

On opening night he didn’t have enough money to fill the cash registers, so the waitresses chipped in their own money to make change.

Snow’s concept for his original entertainment complex was based on his fascination with another era in time: “I love Dixieland jazz,” he says. “I love the lifestyle, I love the airplanes, I love the skywriting, I love the biplanes, I love the clothes, I love the culture, I love the buildings, I love the artwork.”

Almost 50 years later, the good times continue to roll at Pensacola’s Rosie O’Grady’s and its Seville Quarter home.

“Keep the meter running”

“I was up buying a T-6, which is a big skywriting airplane that was used as a fighter trainer in World War II,” Snow begins, leading us into the story of how he wound up in Orlando.

He was in Lawrence County, Mass., negotiating the sale of the airplane from aviation pioneer Harley Mansfield, when a winter snowstorm grounded air travel. As a result, Snow spent the next three days learning how to skywrite from one of the “last skywriters in the world.” It’s a bittersweet memory: Mansfield died just a few weeks later.

Flying the airplane back to Pensacola, Snow encountered the same weather system that had kept him grounded up north. He was diverted to Orlando, where he reconnected with an old acquaintance – a former Marine aviator and Dixieland jazz aficionado who urged Snow to open a Rosie O’Grady’s in Central Florida.

After two days of unsuccessful explorations for a potential site, Snow was headed toward the airport in a taxicab when he asked the cabbie if there was anything historical in Orlando. The driver replied nonchalantly, “We’ve got an old railroad station” on Church Street.

Despite being just a block from the airport, Snow insisted they turn around and drive downtown to check out the historic railroad depot. He found a Victorian building that had opened in January 1890 and had not served passengers since the 1920s. Although the original architecture had been modified and the station was showing its age, Snow told the taxicab driver to “keep the meter running” so he could look around.

“I looked down the street and saw Bumby Hardware, and it was a Salvation Army,” he recalls. “I looked in every window and walked around that area – I left the meter running for an hour and a half, and the cabbie says, ‘I hope you’re good for this,’ and I said, ‘Mister, you’ve been more help than you’ll ever know.’ ”

Seeing the potential in the “bones” of the one-time thriving commercial corridor on Church Street, Snow almost immediately started to implement a plan to duplicate the success he had created in Pensacola.

“The smartest people and the most talented”

Despite the success of the Seville Quarter, Snow had to find a way to get his concept off the ground in Orlando. He took a job as a pilot flying mail from the Panhandle to Orlando in an “old Beech-18” airplane. He flew all night from Pensacola to Fort Walton Beach to Jacksonville before landing in Orlando in the morning.

This schedule allowed Snow to plan early-morning business meetings to pull together a deal to launch his downtown business. Church Street Station started a block west of the depot, at the former site of Slemons Department Store and the Orlando Hotel, which Snow rented for $250 a month. On July 24, 1974, Rosie’s O’Grady’s Good Time Emporium opened there for business and launched a renaissance of Orlando’s aging downtown.

Snow credits the success of Rosie’s in both Pensacola and Orlando with local support, estimating that although residents made up only about 35 percent of the business, “the locals are what gave us credibility.”

Area residents filled in during slow tourist times of year, and word-of-mouth recommendations from Orlandoans helped build Rosie’s reputation. Soon Snow added other venues: Apple Annie’s Courtyard in 1976, Lili Marlene’s Aviator’s Pub and Restaurant in 1977, and Phineas Phogg’s Balloon Works in 1978 before turning his attention to the south side of Church Street.

Eventually, Church Street Station was publicized in the New York Times and Wall Street Journal and, Snow says, attracted 3.5 million visitors annually at the peak of its popularity.

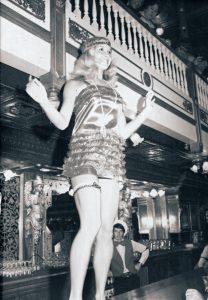

“I never built the thing to make money,” he says. “All I did was make it as beautiful as I could, surround myself with the best-looking people I could find, the smartest people and the most talented people, and let them do their thing.”

Staffing was critical, and from employees’ initial orientation in a restored 19th-century train car, staff members were “immersed in the whole culture from the very beginning,” Snow recalls.

“I challenge you to find anyone who worked at Rosie’s, to find one who wasn’t a very outgoing, spectacular person,” he says. “Most people would tell you it’s the best job they ever had in their life.”

Snow’s attention to detail led to the hiring of skilled craftspeople, and the need for workshops and construction-storage areas led to the Church Street Station property eventually spreading from Pine Street to the south side of State Road 408 – landholdings cobbled together from 30 separate real estate transactions.

“When we were goin’ and blowin’”

Just as Snow put Church Street Station on the map, he worked hard to make downtown Orlando interesting and lively. He improved the streetscape with the hexagonal pavers you still see in downtown today. He lobbied the mayor for police officers mounted on horseback, supplied the city with its first police horse, and added a watering trough for the horse to drink from.

Celebrities flocked to Rosie’s. Bob Hope celebrated four birthdays there. Stars such as Martha Stewart used Snow’s personal train car as guest quarters.

In 1990 Snow sold Church Street Station to Constellation Holdings as he turned his attention to recreating the same concept in Las Vegas. The last Dixieland show at Rosie O’Grady’s in Orlando was in 2001, and today the building is a restaurant.

“When we were goin’ and blowin’,” Snow says – using an old east Texas expression – Church Street Station “had such a reputation.” In its prime in the 1980s, it was one of the premier attractions in Florida. “Lili’s was the top-grossing restaurant in the state until Hard Rock,” Snow says, and you can hear the sadness in his voice when he adds, “The hardest part was seeing it dismantled.”

Today, downtown Orlando is a cultural hub and the center of vibrant nightlife and major sporting events. The man who saw the latent potential in a forlorn stretch of dilapidated businesses and reinvented them into a magnet for millions ends our conversation with the observation that “there’ll never be another Church Street Station.”

Article by Rick Kilby from Reflections magazine, Summer 2016.