By Whitney Broadaway from the Spring 2020 edition of Reflections magazine

In 1862, in the middle of the Civil War, Gustavus Christopher “Gus” Henderson was born near Lake City, Florida. His mother was black, but not much is known about his father, who may have been white. He was raised solely by his mother, who instilled in him a deep-rooted set of morals; she died when he was 10 years old, leaving him alone in the world.

He worked for an itinerant white tinsmith to make ends meet while he was young, but he never allowed himself to neglect his education. By night he taught himself to read from the Bible and the works of Shakespeare. As a young man, he spent several years in farming, but he was not content and eventually found a position with a New York company as a traveling salesman.

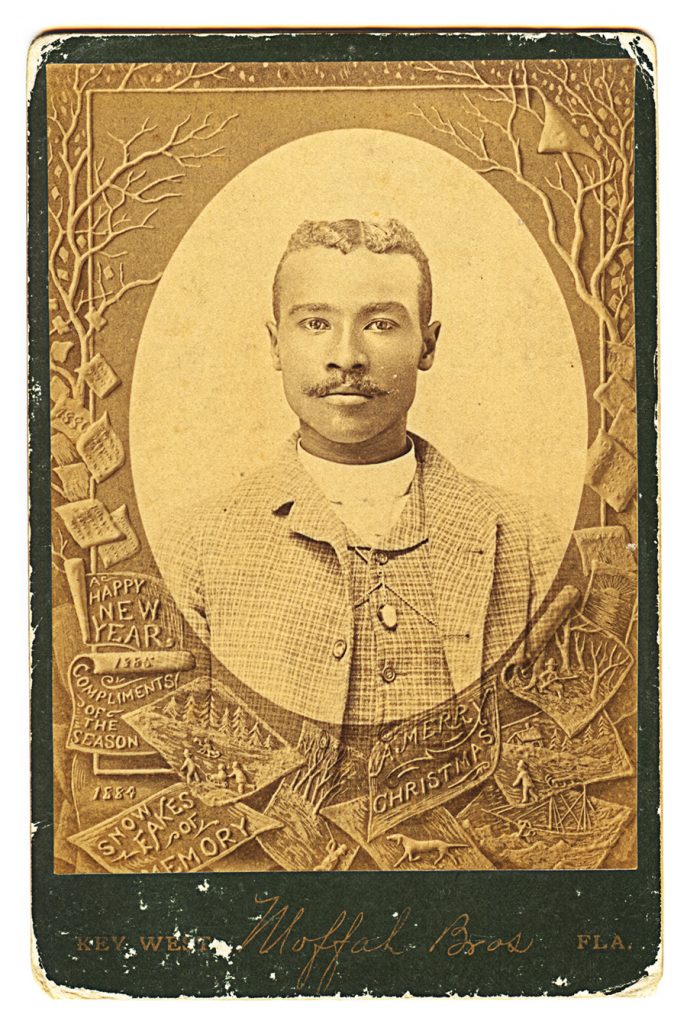

Henderson proclaimed himself to be Florida’s first black commercial tourist. He traveled widely and “met with success wherever he went,” he later recalled. The portrait of him in the History Center’s collection was taken at the Moffat Brothers’ Key West photography studio in 1885 during one of his business trips. After only five months, the firm asked for Henderson’s resignation. When pressed for a reason, they admitted that while he was one of their best salesmen, they had learned he was black and several disgruntled white salesmen were putting pressure on the firm to have him removed.

A new start in Winter Park

After a disappointing end to his sales endeavor, Henderson relocated to Winter Park in 1886, a formative time in the town’s history. Winter Park co-founder Loring Chase, whom Henderson came to admire greatly, and Chase’s business partner Oliver Chapman had only just begun creating the town in 1881, but it was growing quickly. The extravagant Seminole Hotel opened the year Henderson arrived, and Rollins College opened the year before.

With the intention of setting up a business that offered general printing services, Henderson moved into Hannibal Square, the section of town that Chase and Chapman had planned to house black residents. At the same time, Winter Park was seeking official incorporation as a town but was not having luck gathering a quorum for the vote. Of its 297 black residents, 64 were registered voters, while only 47 of its 203 white residents were registered to vote. In the post-Reconstruction era, politics were closely tied to race.

The Republican Party was responsible for the Emancipation Proclamation and led Reconstruction with the goal of moving the South’s black population out of slavery and into citizenship. The Confederacy had grown out of the Democratic Party, which now pushed back against the federally regulated Reconstruction initiatives and preferred that state and local governments be self-governed.

Loring Chase, a Republican from New Hampshire, was a driving force for the party in Winter Park, while John C. Stovin led the Democrats. Most of the black residents of Hannibal Square were loyal not only to the Republican Party that was behind their freedom but also to Chase, who had sold property or rented housing to many of them and also provided much of their employment.

The incorporation of Winter Park became a political battle, and Hannibal Square was the key. White Democrats were afraid that if Hannibal Square was included in the town’s boundary lines, Chase would have complete control. Many Democrats began a whisper campaign among the Hannibal Square residents, telling them that incorporation would be a burden to them and persuading them not to come out and vote. As a result, two voting periods went by with most of the black citizens absent. This meant that the two-thirds of registered voters needed for incorporation weren’t present.

Community officials agreed that the town’s boundary lines should shrink to require fewer voters to be in attendance. They drew up a new, slightly smaller, town map and scheduled the vote for October 12, 1887. At the same time, another map was drawn by concerned Democratic citizens that cut out a large “U” shape in order to exclude Hannibal Square. The vote for this map was scheduled for October 13.

In an editorial in the Lochmede, Winter Park’s only newspaper at the time, John C. Stovin urged citizens to vote to incorporate without Hannibal Square. He claimed that including Hannibal Square would be handing votes to a transient people who did not own land or call Winter Park home and would recklessly turn the town wet (meaning allowing the sale of alcohol). The next issue of the Lochmede contained an extremely firm and eloquent rebuttal from Gus Henderson. He noted that while many Hannibal Square residents didn’t have strong feelings against alcohol, they had all agreed to vote to dry out of respect to Winter Park residents with strong concerns. He also argued that most black registered voters owned land in Winter Park or were otherwise committed community members. He invited Stovin to meet him for a tour of all the grand houses and businesses owned by black residents.

On October 12, 1887, after much hard work to dispel the rumors against incorporation, Henderson led a veritable parade of Hannibal Square residents to vote. For the first time, a quorum of voters was gathered, and the citizens voted to incorporate, including Hannibal Square. Two black residents, Walter B. Simpson and Frank R. Israel, were selected to serve on the town council; as of today, they remain the only people of color ever to hold an elected office in Winter Park.

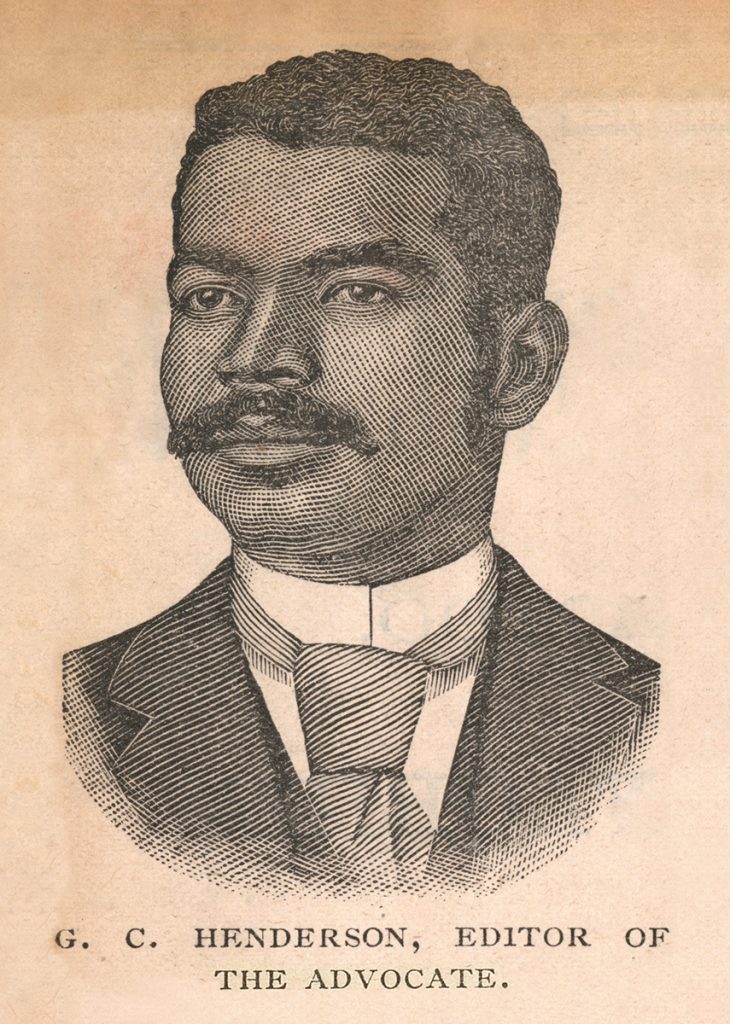

Henderson continued to write editorials and an occasional society column for the Lochmede, until he founded his own newspaper, The Winter Park Advocate. His company began with twelve members, but by the time the first issue came out on May 31, 1889, only two employees had gone the distance with him: his editor, S. A. Williams, and a typesetter named Walker. The Advocate was the second black-owned newspaper in the state and soon became Winter Park’s only source of news when the Lochmede published its last issue on June 28, 1889.

Both black and white residents read Henderson’s weekly paper. In fact, the most abundant source of surviving clippings can be found in Loring Chase’s personal scrapbooks, housed in the Rollins College Archives. However, very few copies of the Advocate survive today. The History Center has one copy, which was originally laid in the cornerstone of the 1892 Orange County Courthouse. Two other copies reside in the Winter Park History and Archives Collection at the Winter Park Public Library.

By 1890, Henderson was no longer just the paper’s manager – he was now the editor, a reporter, collected subscription fees, and sometimes even helped to set type. After a proposal from Henderson, the town council agreed to strike up a business deal with the paper, allowing their minutes to be published in the Advocate for a fee, ensuring the paper’s longevity and expanding its utility for residents.

The paper’s articles and society updates were mostly of a positive nature. Henderson was very keen on promoting Winter Park as the very best in all things, but he was also quick to stand up against political injustice and would not waiver in the face of threats, of which he received plenty. One such was mailed to him by John C. Stovin in 1890. Later, around 1906, he was threatened by a white mob outside of his Orlando home.

Unfortunately, Stovin and the other Democrats did not concede after the 1887 vote, and a petition to remove Hannibal Square from the city limits was eventually granted by the state legislature in 1893.

A move to Orlando

Gus Henderson continued to operate his Winter Park newspaper until at least 1899, but it is likely that he and his wife, Martha, moved to Orlando shortly after the de-annexing of Hannibal Square, judging from rumors as early as 1894 that Henderson was planning a new paper venture in Orlando. In 1898 Henderson was appointed one of seven division deputies in Florida for the Internal Revenue Service, for which he listed his employment and residence as Orlando.

Henderson established the Florida Christian Recorder in 1900 – Orlando’s first black-owned newspaper. It was a weekly publication and possibly related to the African Methodist Episcopal Church’s papers: The Christian Recorder, Southern Christian Recorder, and Western Christian Recorder. Henderson was an active member of Orlando’s Mount Olive AME Church, and the newspapers certainly shared the same naming convention, but Henderson’s publication seems to have been fairly independent. This seems especially likely considering a proposal from R. S. Quarterman in 1915 to save the church money by closing down the Southern Christian Recorder and to allow Henderson’s paper to fill the void, since it was already one of the preeminent black publications in the South.

Henderson published the Recorder out of an office at 502 Patrick Street – now the corner of Division Avenue and West Pine Street. The office was next-door to the Henderson family’s large, two-story home with a wraparound porch; the back yard contained a small chicken coop and citrus trees. The Hendersons also built rental properties facing Division, just behind the printing office. Sadly, even though the Florida Christian Recorder was published for more than 15 years and lauded several times over in other papers, no copies have been found so far – not even clippings or microfilm.

Gus Henderson remained active in politics after relocating to Orlando, and quickly became an influential voice at local and state Republican conventions alongside fellow party members such as H. S. Chubb, mayor of Winter Park, and Judge John Cheney, along with his son Donald, and W.R. O’Neal, pioneers from the North who were both involved in nearly everything happening in Orlando in its early years. The Orlando Sentinel summary of the 1916 Orange County Republican convention lists Henderson as the convention secretary alongside chairman W.R. O’Neal.

Henderson was only 54 years old when he died of consumption in 1917, and the Florida Christian Recorder blinked out of existence along with its creator. His wife, Martha, continued teaching at Jones High School, and their four children, all having graduated from prestigious colleges, exemplified Gus and Martha’s dedication to education. Gus Henderson was the embodiment of the “self-made man”; from his humble beginnings, he became one of the South’s most eloquent editorialists and left an indelible mark on Central Florida history.