Orlando’s first taxidermist was no stranger to live creatures

by Lesleyanne Drake, from the Fall 2019 edition of Reflections magazine

Augustus Milton Nicholson was in his 20s when he arrived in Orlando around 1885. At the time, the city already had doctors, blacksmiths, teachers, hoteliers, and even an undertaker. But there was one profession Orlando was still missing: a taxidermist.

According to Eve Bacon’s Orlando: A Centennial History, Nicholson was the first taxidermist in Orlando. His shop, located somewhere along West Church Street between Orange and Garland avenues, had a large pen in back containing live snakes and other reptiles that Nicholson caught in the Florida wilds.

From Snakes to Pelicans

Sometimes Nicholson would sell the creatures he caught, such as when he reportedly received an order for 100 live snakes for a traveling show. Other times he would milk the snake venom and sell it for laboratory research. He was only ever bitten once, Bacon writes – by a rattlesnake on the finger. Though his arm swelled to the elbow, he recovered after a few days with no long-term effects.

Nicholson developed his own techniques for capturing snakes, as described in E. H. Gore’s History of Orlando. If they were not poisonous, he would simply roll them up and put them in the pockets of his hunting jacket.

For rattlesnakes, he applied a little more caution. Using a noose at the end of a 5-foot pole, he would place the animal in a sack with a double layer of cloth, thick enough that its fangs couldn’t pierce the fabric. However, if Nicholson was in a pinch, Gore states, he would distract the rattler by dangling a handkerchief with one hand while grabbing the back of its neck with the other.

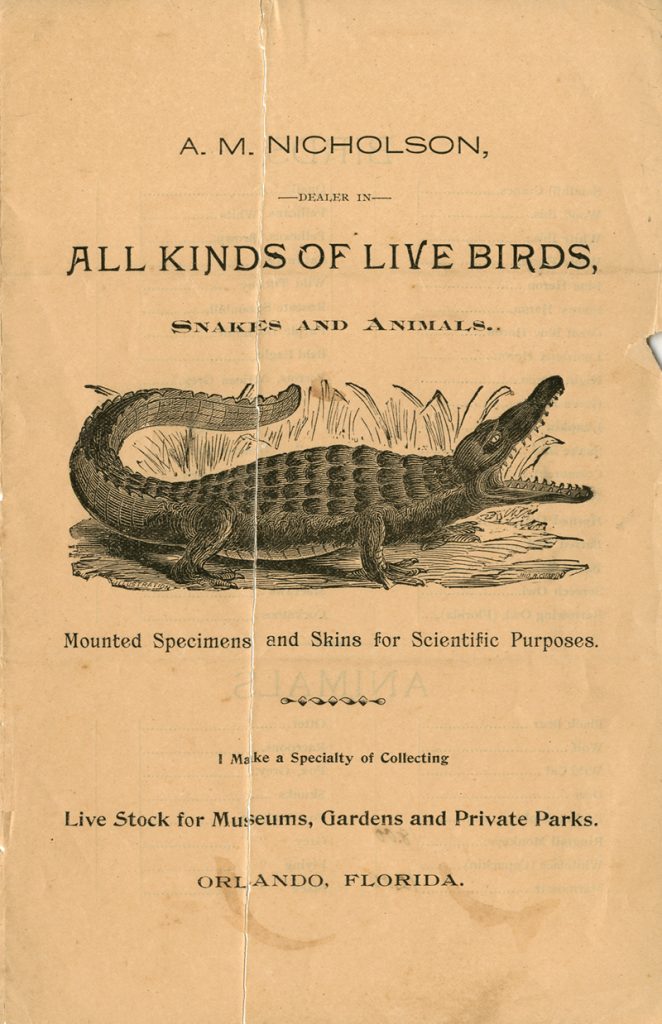

Snakes weren’t Nicholson’s only specialty. In a brochure in the History Center’s archives, he advertises a wide variety of animals for sale – both “mounted specimens and skins for scientific purposes” and “livestock for museums, gardens, and private parks.” In addition to 14 different species of snakes, the brochure lists various mammals, large and small, commonplace and exotic. Alligators have their own feature section, priced by length. A one-foot baby alligator cost 50 cents, while a 12-foot alligator was $50. It is unknown whether this price referred to live animals or mounted specimens.

Birds adorn another page in Nicholson’s pamphlet, listing 38 species available for sale. During the late 19th century, exotic birds were in high demand, especially the long, curved, white plumes of egrets and herons, which were all the rage in ladies’ hats. The fashion fad resulted in more than five million birds being killed annually for their feathers, until a conservation movement, led chiefly by the Audubon Society, successfully advocated for changes in state and federal laws that would protect the endangered birds.

Though these laws cut into Nicholson’s business, it did not necessarily put an end to his trade in birds. In 1914, Nicholson returned from Tampa Bay with 19 large pelicans in coops. This was such an unusual sight for passengers on the Atlantic Coast Line railroad that the story found its way into Orlando’s Morning Sentinel. Some of the birds Nicholson would keep, and others would go to a zoo, he told the newspaper.

Tales of a Taxidermist

In addition to making belts and souvenirs out of the reptile skins, Nicholson dealt with the snakes, fish, alligators, and other animals that locals and tourists alike brought him for mounting. From the 12-pound black bass caught by a St. Louis tourist to the 5-foot, 3-inch rattler that was too busy trying to swallow a “good-sized rabbit” to bite the laborer who stumbled upon it, what better way was there to remember surviving Florida to New York, including turtles, rare geckos, and snakes. Nicholson, who was very impressed with Dickerson and disappointed to see her leave, recounted the expedition in an article for the Sentinel, lamenting, “I had no time to even show her about the city. She is a lady of only business, business, business.”

Though wildlife was how Nicholson made his living, his writings reveal a passion for nature. When an editorial appeared in the Orlando Evening Star speculating that squirrels were to blame for driving the birds away and that something should be done, Nicholson wrote his own editorial defending the creatures: “For nearly thirty years I have been a roamer of the field and forest. I think I am a pretty close observer along nature’s lines. Some years ago, we did not have towering dense trees for these birds to sit in. Today there are numbers of little birds that flight about in these oaks and sit in their tops and sing and the breeze will carry their notes forever, away from our ears. And unless one takes the time to stop and look closely for them they would never be seen or heard. . . . Don’t blame the poor cunning little squirrel.”

Instead, Nicholson asked readers to consider the idea that human interference is the reason for fewer birds. He suggested that it might help to ban the sale of air guns, which in his view, are useless for legitimate hunters and have no other purpose than to allow young boys to torment birds and other animals for fun. He concluded, “It is as much pleasure to me to see the squirrels and watch their pranks as it is to hear the birds sing, and I hope there will be no action taken to do away with them.”

Nicholson and his wife, Alice, were the parents of five children, two girls and three boys, who grew up surrounded by animals. He passed his love of nature on to his son Delmar, whose effort to create a zoo in Orlando and educate the community about nature and endangered animals is its own story.

While Nicholson kept his animals at his shop on West Church Street, according to Gore, he was “notified to remove them from the business section of the city” after a large alligator knocked down a part of the fence and escaped, along with Nicholson’s collection of snakes.

After that, Nicholson moved his business to present-day South Division Avenue, which was, Gore notes, considered “the country” at that time. Though there were several more animal escapes over the years, including a wildcat that found its way into a neighbor’s henhouse, Nicholson lived and worked on Division Street until his death in 1926 at the age of 66.

Nicholson’s story reflects both the exploitation as well as the wonder, appreciation, and discovery of Florida’s natural environment.

Now, a century later, we still struggle to preserve Florida’s ecosystems. Looking back at Central Florida during Nicholson’s time reminds us of how far we’ve come, how far we still have to go, and how important it is to stop and listen to the birds.