Photo courtesy Maria Esquinca

By Cheyenne Stastyshyn, Public Programming Coordinator

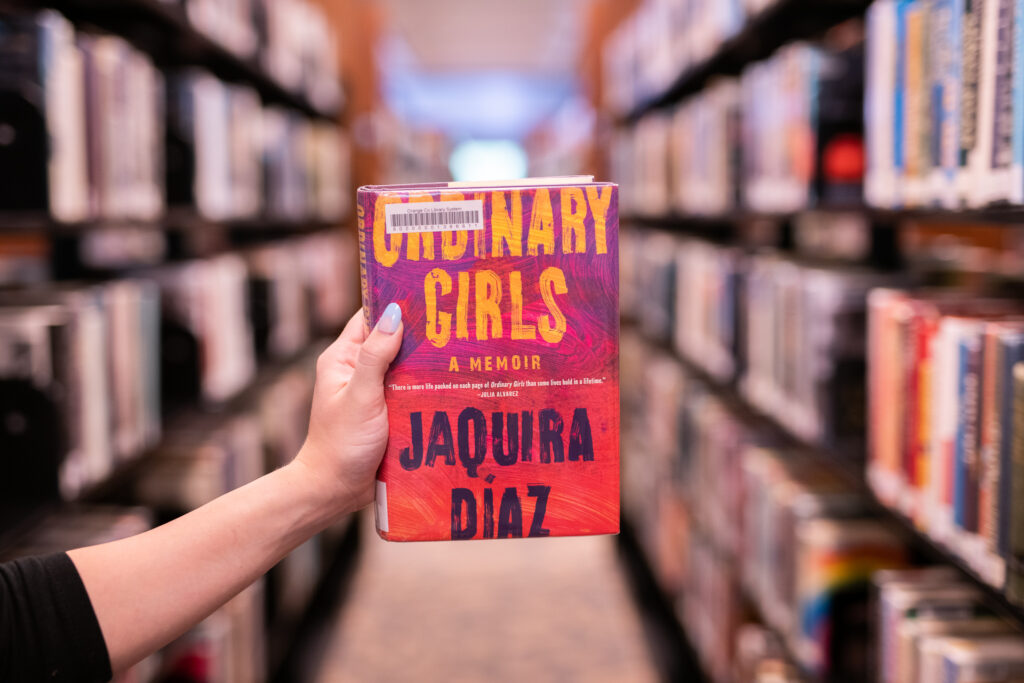

This month our Reading Through History book club selection is Ordinary Girls, a fearless 2019 memoir by Jaquira Díaz that received many literary honors. It won a prestigious Whiting Award and a Florida Book Awards Gold Medal and was a Lambda Literary Awards finalist, an American Booksellers Association Indies Introduce Selection, a Barnes & Noble Discover Great New Writers Selection, an Indie Next pick, a Library Reads pick, and a finalist for the B&N Discover Prize. The book has been optioned for television and is currently in development at FX with Díaz as co-executive producer.

A graduate of the University of Central Florida, Diaz was born in Puerto Rico and grew up between Humacao, Fajardo, and Miami Beach. Ahead of the book club’s gathering on August 17, she was kind enough to give us insight into her life and her book by answering some questions for us.

Your excerpt about running away from home and what followed at Santa’s Enchanted Forest really resonated with me and my experiences growing up. Being an adult and moving forward from these experiences, I sometimes forget that things like that happened. What advice would you give to a teenager who is experiencing similar things?

Jaquira Díaz: When I think of what advice I would give a teenager, I guess I’m always thinking about what advice I would give my teenage self. I wish I’d had someone, anyone, to turn to, to explain the things that were happening to me, to ask for advice, for guidance, for help.

So I would say, find someone, an adult, who knows what to do. Someone you can trust, someone who can help without judgement. I had a counselor, a court-appointed counselor, who I talked to, but I didn’t fully trust her, and I didn’t tell her all that was going on in my life. Now, in hindsight, I wish I had. I also had a school counselor, Ms. Gold, a person who was fully available to me, who never judged me, who was always there to guide me in making better decisions. I didn’t tell her either. I would tell teenage me to ask for help, be honest about what’s happening. And if the person you tell makes you feel judged, or if they do not understand, tell someone else.

In your writing you seem to always carry hope and a dream that one day things will be better. It’s inspiring because even so young, going through everything you went through, you always knew that you wanted better. Where do you think that motivation for a better life comes from?

I can honestly say I wish I knew the answer to this question. I think in part that hoping for a better life comes from suffering, moments when things get so bad that you wish for something better, when you feel like this can’t possibly be the way things will always be. And I think another part was my abuela. She was a constant presence in my life—she raised us, but also, she was kind and loving and uplifting. She wasn’t perfect, but moments with her brought me calm. I was happy when it was just the two of us. I forgot about the rest of the world.

Now that you are an adult, can you speak to how you created a safe and fulfilling life for yourself? What specifically was the turning point for you where you felt like you were able to finally grasp onto the dreams you always dreamed? How did your dreams of the future change as you got older?

The truth is there was not one turning point, or one event. There were many turning points, small and huge. And each one got me closer to the life I wanted. There were moments I thought of as huge at the time, like getting my GED, that would turn out to be quite small, but that led me in the right direction. Getting my GED led me to taking classes at Miami Dade College, and that led me to creative writing classes, and that led to me earning an AA in English, and that led me to apply to the University of Central Florida. . . . There was no single turning point, because I never followed a single path. There was the time I spent in the military, the years I spent working as a pharmacy technician.

All of these things led me to the life I have now, yet there was not a direct path. I stumbled—I was always stumbling, coming across obstacles, experiencing setbacks. I had to work while taking college classes, so it took a really long time. I didn’t know if I would ever be able to call myself a writer, but I did know that I was already writing, and that meant something to me. I didn’t know if I would ever make money from writing, but I knew that I could be a teacher, and then I taught my first creative writing class and loved it.

I think it’s really important to share this aspect of my journey, because we tend to romanticize the “resilience” or “survival” narrative as something that requires something like superhuman powers, or one huge turning point, or a savior, and that was not my life at all. I tried things, and I failed at them. I had jobs, multiple jobs, and I failed at them. I failed out of college and went back years later. I left one MFA program and started another one years later. I learned from these failures, which is what’s important. You will fail, and that’s okay. You get back up and you try again.

My life changed when I stopped thinking in terms of dreams and started thinking of goals—achievable goals. Yes, these were dreams. But I had to find a way to see these dreams as achievable, and think of realistic ways to make them possible. I had to break these down to small steps—going to college, writing stories, sending these stories out, reading as much as possible. And again, risking failure, and allowing myself the grace to fail, to try again.

You write about how Papi loved books and wrote quite a bit. The influence of literature definitely left an impression on you. Can you speak to your relationship with books growing up? Did you write about your day-to-day life while you were growing up? Did you pull from events you wrote about as a young girl when writing Ordinary Girls?

Growing up, I spent so much time in the library! I loved (and love) the library so much. Librarians are superheroes. If I wasn’t a professor and a writer, I think I’d be a librarian. I’ve always lived close to a library. In Miami Beach, our apartment was within walking distance—my spouse and I lived just five blocks from the public library. And now, our apartment in New York is directly across the street from the library. (If there’s no public library, does it even feel like home?)

It’s always been this way for me, and I think that was my father’s influence. I loved books because he loved books, but we couldn’t afford them. The library kept me alive, not just literature, and not just books. It was this place where books existed, a kind of magical place of refuge and community. Growing up, I read like my life depended on it, but often in secret. My friends had no idea I loved books. We didn’t talk about books. But in the library, I could be fully, unapologetically, myself.

I’ve kept journals my whole life, since I was a child. I kept a trunk full of old composition books filled with stories and poems and essays, chunks of my life, anecdotes, fairy tales, horror stories, letters to friends, notes about stories that were on the news—I always wrote compulsively. I turned to these journals while I was writing Ordinary Girls, and while I didn’t use any of the material, I mentioned some of it in the book. In a chapter called “Home is a Place,” I mention a story I kept writing in my journals: the legend of El Pirata Cofresí. It was a story passed down to me by my father (which also exists in books) but as a child, I took it on as a creative project, the retelling of this story again and again. I kept writing this story, different versions of it, re-gendering the pirate as a girl, re-imagining versions that felt like the kinds of stories I wanted to read. I was already coming to the conclusion that people like me did not exist in books, and that it would be my job as a writer to write myself into a sort of literary landscape. I didn’t have the language for it, but it’s what I was doing.

You have beautiful hair, but in your book you write about how your maternal grandmother would say cruel things about your Blackness, specifically wanting to shave off your “bad hair.” How did your relationship with your maternal grandmother affect your own identity and was it challenging to accept your physical identity?

It wasn’t challenging to accept my physical identity—I didn’t feel like there was anything to accept, I just was—or to love my Blackness and my Black family. But it was challenging to live with racism in my own family, it was heartbreaking to know that a person so close to me did not love everything about me, did not love my Black family, and that she fully hated Black people. As a child, it was often terrifying to be related to her, to hear her tell her stories and realize that there was something about this person, my own grandmother, that was hateful and dangerous.

And while it wasn’t challenging to accept my own physical identity, it was hard to live with the reality that other people didn’t see me, did not understand who I was, or what it felt like to live in my skin. I wanted people to see my full self—that I was Black and Puerto Rican, that I was fully bilingual, that I was raised by a Black grandmother in a Black family. We had to learn early on that the world would not fully see us, but also, that when white people did see us, it was not always for the right reasons.

There was something I took on as a kind of responsibility when I was a little kid, living in a world where people did not read me as Black, and often people assumed that my abuela was my nanny: to correct them, to let them know, to affirm myself as her daughter, her granddaughter, her kin, to say that she was both my grandmother and my mother, because that’s what she was. But I think this also made me hard, for a long time. There is something that happens to a child when she is forced to live in a world where people don’t read her as Black and so she has to listen to all the things white people say about Black people. The things people have said in front of me, or around me, because they didn’t know I was Black. . . .

You talk about how Papi taught you about Puerto Rico’s colonization and your family’s African ancestry. How did learning about this influence your own identity? Can you speak to how this influenced what it was like moving to Florida knowing this history?

I grew up in a family of people who love history and books. I was raised to know our history, but also to know that there were things that schools would never teach me, so I had to look elsewhere. My father had been an activist for Puerto Rico’s independence, and he learned this lesson while he was in school, and passed it down to us. We learned about colonization and genocide and slavery early on. We had many conversations about power and history and the suppression of Puerto Rican thinkers and activists. I come from people who do not forget—we pass stories down.

Moving to Florida, specifically to Miami, a place with a deep and painful history of segregation, was like a fracturing of the self. Growing up a mixed queer kid in Miami was to live in a violently segregated and homophobic city, negotiating fragments of yourself, dealing with the shit people said to you or said in front of you because they didn’t know you were Black, or queer. I felt most seen by a friend who was Afro-Indigenous Honduran, and a friend who was Black Cuban, and a friend who was Haitian and gay. But my other Black friends and my other Latine friends did not mix. They all lived in different neighborhoods and ran in different circles. There were aspects of my life I kept separate. To be seen as my full self, in Miami? That was unimaginable to me at the time, and quite frankly still is.

And while passing has never been something I want—the idea of passing feels like inflicting violence on myself—being light-skinned, not read as Black, has meant that my life has been considerably easier than it is for dark-skinned and visibly Black folks. Reckoning with anti-Blackness and internalized racism is a lifelong process. It’s not something that you just do and suddenly anti-Blackness and racism just goes away. You have to keep learning about it, noticing it, finding it, naming it, undoing it, making others aware of it, thinking about it, writing about it, because everything in our world is built on it. All the systems and industries in this country—from education, to the medical system, to prison systems, to policing, to publishing—are built on ideas of white supremacy, and we have people in power who are actively trying to maintain the status quo, and actively trying to keep the rest of us unaware and uneducated.