Originally published in the Winter 2017 edition of Reflections From Central Florida

As American cities grew in the late 19th century, a distinctly new type of building rose, fueled by a “unique combination of industrialization, business, and real estate,” writes architecture critic Ada Louise Huxtable.

It was no longer necessary for buildings to develop slowly and heavily from the ground. Advances in metal framing that could hold the weight of a non-supporting façade, along with fireproofing and passenger elevators, gave rise to the modern American commercial building, dubbed the “skyscraper” – a subject of both scientific and popular fascination.

The new building type had roots in various cities but flowered especially in Chicago, where the first example of true skyscraper construction, the ten-story Home Insurance Building, rose in 1884-1885 (it was demolished in 1931) – the same period when Orlando’s commercial core was recovering from a devastating fire in 1884 and was being rebuilt in brick and stone.

Recovering from another blow – the Great Freeze of 1894-1895 – the city entered the 20th century with a population of 2,481 and a skyline dominated by the tower of Orange County’s 1892 courthouse. By late 1914, Orlandoans could enjoy the view from a fifth-floor roof garden atop Yowell-Duckworth’s department store at 1 S. Orange Ave.

That was about as high as it got – until the booming 1920s, when Orlando exploded with growth. Beginning about 1921, “people were swarming into Florida like locusts,” historian Eve Bacon writes. The city’s population of 9,282 in 1920 would double in five years and nearly triple by 1930.

And the new skyscraper style pioneered in Chicago in the 1880s came to Orange Avenue, in a dizzying burst of construction.

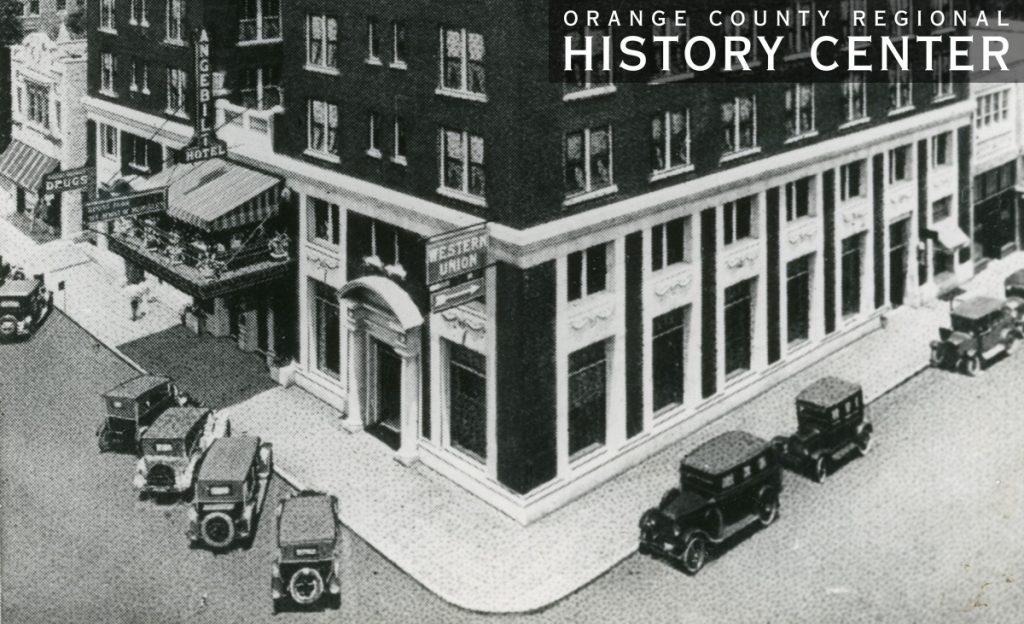

Beginning in 1922, an eight-story addition took the venerable San Juan Hotel to new heights at 32 N. Orange Ave. (it was demolished in the 1980s), and soon the “skyscraper” rank of at least ten stories was reached by three structures that still grace Orange Avenue: the Angebilt Hotel building, which opened in 1923, and the former bank buildings at 1 N. Orange and 100 S. Orange, which opened in 1924.

Buildings like these, some of the first American skyscrapers, were inspired by efficiency and expediency – by the need to build quickly to meet commercial demands – but they are “as handsome as they are utilitarian,” Huxtable writes. “They possess a great strength and clarity that gives them remarkable expressive power.”

The Angebilt

In late June 1921, developer J.F. Ange announced plans for a million-dollar, 240-room hotel at the northeast corner of Orange Avenue and Oak Street (now Wall Street).

Orlando’s own Murry S. King, Florida’s first registered architect, designed the elegant hotel, which broke height records when it opened in March 1923 (Ange sold his interest shortly thereafter). It’s now an office building at 37 N. Orange.

King, who moved to Orlando from Pennsylvania in 1904, designed many prominent Central Florida buildings, including the 1923 Albertson Public Library and the Orange County Courthouse that now houses the History Center.

Shortly before the Angebilt’s opening, an Orlando crowd gazed upward in amazement as Harry Gardiner – billed as “the Human Fly” – scaled the building to raise money for a home for “the friendless girls of the city.” NuGrape soda sponsored the event.

Gardiner began his feat at 7:30 p.m., enthralling a crowd estimated at 10,000, according to news reports. He kept the crowd in suspense for 90 minutes while he ascended and descended the eleven stories, occasionally hanging from a windowsill by his fingertips.

The State Bank of Orlando & Trust Company Building

The State Bank of Orlando was organized in 1893 with Louis Massey as president and T. Picton Warlow as vice-president. In 1919, it became the State Bank & Trust Company and also acquired the northeast corner of Orange Avenue and Central Boulevard, where it debuted its new skyscraper home in 1924 at 1 N. Orange Ave.

Constructed by A.G. Bentley, the ten-story building was designed by W.L. Stoddart, a prolific architect of urban hotels with offices in Atlanta and New York who had also designed the eight-story addition to the San Juan Hotel.

When the building opened in 1924, the bank occupied the first floor and mezzanine; the upper levels were rented as offices to tenants including attorneys, real estate brokers, dentists, manufacturers, and a Christian Science reading room.

The bank closed in 1929, and in 1933 the Florida Bank at Orlando acquired the property. Later, it housed Orange County offices, and in 2002 served as the temporary home of Florida Agricultural and Mechanical University’s College of Law.

Orlando Bank & Trust Co.

Often known as the Metcalf Building for H.W. Metcalf, who purchased it in 1930, this ten-story early skyscraper at 100 S. Orange Avenue was dedicated in 1924 as one of the city’s most fashionable addresses. The builder was A.G. Bentley.

The ground floor was home to the Lucerne Pharmacy until 1926 and in 1936 to the Liggett Drug Store. Metcalf bought the building after the bank failed during the Great Depression.

In the mid-1980s, an extensive $2.5 million renovation uncovered elements of the building’s original ornamentation when decades-old concrete panels were removed.

Stripping off layers of linoleum, workers also revealed an Art Deco terrazzo floor at ground level and an elaborate second-floor ceiling featuring painted plaster rosettes.

The plasterwork compared well with similar work in historic New York buildings, master plasterer Vince Sciandra noted in 1985 about the discoveries – “particularly with what you find around Broadway and Wall Street.”