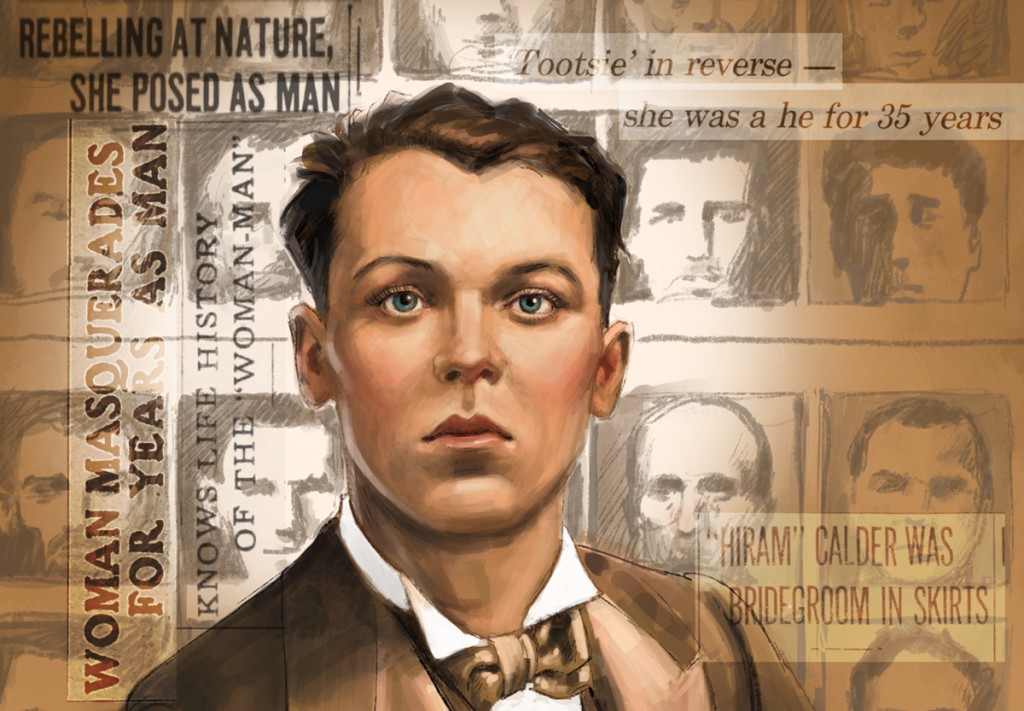

A revelation after an Orlandoan’s death in 1914 shocked the city. Now, new research reveals much more about one of Central Florida’s enduring enigmas. Illustration by Thomas Thorspecken.

by Whitney Broadaway, Collections Manager

On the morning of July 11, 1914, Dr. Calvin D. Christ was summoned to the Orange County home for indigents. A 64-year-old Orlandoan, Hiram E. Calder, lay dying of pellagra, a disease caused by a lack of the vitamin niacin. When Dr. Christ arrived, Calder, who was delirious, confessed that he was born a woman.

The news shocked Orlando. Ever since Hiram and his wife, Sarah Calder, had moved to Orlando years before, no one had ever thought to question his gender. Sarah had died four years previously. Calder died two days after Dr. Christ’s visit, on July 13, and the sensational news stories were already hitting the stands. Orlandoans were desperate for answers as to why Calder had lived in “disguise” for so long, and how Sarah could have been his wife if he was in fact a woman.

Intelligence and voting

The Morning Sentinel’s writer was especially impressed with how Calder had blended so naturally into male society, “talking intelligently upon many subjects.” Women’s suffrage was a big issue in 1914, and reporters quickly put together that Calder had enjoyed the then exclusively male privilege of voting for at least 14 years. Many proclaimed Calder to be the first woman to vote in Florida.

All eyes went to Charles T. Hungerford, who had long employed Calder in his bakery at 116 S. Orange Ave. In a 1983 Sentinel article, Donald Cheney, a retired judge and founder of the Historical Society of Central Florida, recalled boyhood memories of Calder at the bakery.

Cheney, who was born in 1889, said he and his chums often stopped at the bakery after school, especially for the homemade candy. Calder was the silent counter man. “He hardly ever talked, hardly ever smiled, just sat there behind the counter,” Cheney recalled. “He dressed very simply, usually without a coat or vest, just a pair of pants and a shirt.”

Upon Calder’s death, Hungerford was as dumbfounded as the rest of Orlando. Calder had begun working for him at the bakery shortly after moving with Sarah to Orlando in 1902 from Highland Springs, Va. The Calders would often leave Orlando in the summer, and it was rumored that they traveled with a circus during these months. Sometime before 1909, the couple moved to Tampa, where they operated a grocery store at 1308 Nebraska Ave.

Sarah Calder died of paralysis in Tampa’s Hampton Sanitarium on Oct. 2, 1910, and was buried in Woodlawn Cemetery in Tampa, where Hiram Calder purchased a lot and placed a white marble monument at the grave, all with the intention of being laid to rest beside her in the future. Calder spent hours at Sarah’s grave, according to news accounts after Calder’s death, and was described as “heartbroken and frantic with grief.” A July 28, 1914, Tampa Tribune article reported that Calder had told the cemetery’s sexton, W. D. Burgess, that “nobody could ever know how much he loved his wife.”

After Sarah’s death, Hiram Calder returned to Orlando and began working at the bakery again. His own health began to fail, and he was soon at the mercy of his friends’ charity, sometimes only able to work a couple days a month. Eventually, he became too sick to remain in his friends’ care and had to be moved to the county home. Doris Topliff, one of the bakery’s new owners, became a frequent visitor. After Calder’s death, the county home’s superintendent gave Calder’s Bible to Topliff; no family had appeared.

The receipt in the Bible

Topliff already knew Calder to have been a devout Catholic. Searching through the Bible, she discovered an old receipt tucked into its pages from St. Joseph’s Union, LaFayette Place, New York City, for payment for “the homeless child” until March 1, 1888.

Believing this receipt to be proof of an illegitimate child, Topliff reported to the press her theory that Calder “made one unfortunate misstep in her early life” and had begun to live as a man to provide for the child. According to this scenario, once the child, Sarah, reached adulthood, Calder began introducing her as Mrs. Calder. In 1914, a Sentinel writer could not believe someone hadn’t put that explanation together sooner, because “it is so logical and is the only theory upon which the deep affection of the two can be explained.” Orlandoans had an answer about the Calder puzzle that made sense to them.

But they were wrong. It turns out the receipt in Calder’s Bible had nothing to do with an illegitimate child; it was for a newspaper subscription. St. Joseph’s Home on LaFayette Place in New York City was actually a boy’s home that sold subscriptions to a publication titled “The Homeless Child.”

For more than a century, the theory about Sarah being Calder’s illegitimate child would be repeated – but now, after months of research, we know much more about Calder than ever before.

The first key to unlocking the mystery came from news reports of a letter by E. L. Flory of Wilmington, N.C., sent to Tampa’s police chief, S. T. Woodward, shortly after Calder’s death. Flory had seen the news about Calder’s death in his local paper in the days after his death, for by this time the story had made headlines across the country, and it reminded him of a story from years before, when he lived in Maryland: a story about a woman named Hanna Calder.

The story of Hanna Calder

Born on January 26, 1850, Hanna Calder was the fourth of six children born to Martin and Nancy Calder, a prosperous blacksmith and his wife who lived on a farm in Harford County, Md. According to friends and family, Hanna Calder was a strong-willed child who began smoking and chewing tobacco in her teens and took great joy in riding horses around the countryside. She attended the county school at North Bend and later the Bethel Academy. Her father believed her to be a good scholar with a bright and ready mind.

Even though she was in no need of money, Calder started a small barbering business when she was in her twenties. She became known as the “Harford County Barber,” riding to and from farmhouses to provide shaves for the men and trims for them and their children. She kept her own hair short.

After a study of several religious works, Calder converted to Catholicism at the age of 29 and began attending St. Mary’s Catholic Church in Clermont Mills. Ten years later, in May 1888, Calder approached a priest, the Rev. J. Alphonse Frederick, to discuss the subject of marriage to Catherine Beall, known as Kate. According to news reports, Calder provided Father Frederick with a news clipping about a case from 1884 to help explain the situation.

The article from four years earlier was about Elizabeth Rebecca Payne of Winchester, Va., who never suspected she was anything but female until she began to notice a romantic attachment toward another woman, the article said. Payne visited a doctor, who discovered, perhaps due to latent development, that Payne was in fact a man. Beginning the transition into a new life as a man, Payne married, began dressing as a man, and took a male name.

Calder sympathized with Payne’s story. Born a woman, Calder noticed a change around the age of 25. It is important to note that this explanation comes from an interview in which Calder told reporters, “I felt I was becoming a man,” but this testimony may still not reflect Calder’s true feelings. In historical accounts of women who have lived their lives as men, the few people who had the opportunity to address their actions often had to curtail their justifications to avoid serious repercussions.

In the world Hanna Calder lived in, a woman loving another woman was unacceptable, but a woman discovering that she was meant to be a man all along – and in love with a woman – that, perhaps, was a situation society could tolerate. Although it seems clear from Calder’s explanation that he identified as male, there is a chance that Calder was doing and saying what seemed necessary in order to marry whom he loved.

The wedding of Hanna and Catherine

After careful consideration, Father Frederick procured a marriage license in the names of E. Hanna Calder and Catherine Beall. But, when the couple arrived for the marriage, Father Frederick discovered that Kate was not yet 18, as he had been led to believe. He insisted on proof of her parents’ consent, for which the couple produced a letter signed by both parents but all written in the same handwriting. Kate explained that her father asked her mother to sign it for him. The priest would not accept the note and suggested he perform the ceremony at the Beall home, but both Kate and Hanna hastily objected to the idea, explaining that Kate’s father was a staunch Protestant and would never allow a Catholic ceremony to take place under his roof. Reluctantly, the couple agreed to postpone the marriage.

Hanna Calder was 38 years old when they finally wed on September 5, 1888 – Kate’s 18th birthday. After the marriage, they returned to their respective families until February 1889, when they ran away to Baltimore. There, Calder reportedly bought a men’s suit and began using the name Howard.

It was only after their disappearance that the families learned of the marriage the year before. According to Hanna Calder’s sister Sophia, Calder had tried to marry another woman before, when she was 18, and it cost their father a large sum of money to clear up the business.

Martin Calder was greatly moved by the absence of his child and worried what the shock would do to his wife Nancy’s already failing health. They were both 72 at the time. On February 21, 1889, less than 10 days after the couple ran away, the Baltimore Sun reported the death of Nancy Calder. Hanna, now Howard, Calder would later tell newspaper writers that he thought this announcement was a ploy to draw the couple out of hiding.

After stashing away in the homes of friends for over a month, Kate began to feel the secrecy taking its toll. She longed to see her family, so Calder sent a letter to reveal their whereabouts. On March 16, detectives escorted Kate back to her family. When reunited with her father, she asked to have a telegram sent to Calder arranging for her to rejoin her husband, but her father refused.

Calder spoke with several reporters following the couple’s separation and noted an intention to appeal to the courts to have Calder’s rights as a husband upheld if the Beall family refused to release Kate. Calder bragged of their cunning in eluding detection, including the time they were upstairs when detectives came to a house on Mount Street and listened in on every word. Even during his courtship with Kate, when their families forbade any communication, they set up a secret “post office” on the road between their houses to leave letters. Reporters characterized Calder as displaying a ravenous consumption of tobacco and a readiness to pull a gun and “secure an apology” when an offensive comment was made.

When reporters visited the Bealls to ask Kate’s feelings, she replied, “I am happy to be once again with my mother and my sisters . . . but I still wish to rejoin him. I know the difference between filial and conjugal affection, and I feel both.” And when asked about the secret post office, she grinned, saying, “Yes, we were quite too sharp to be caught.”

The couple did not continue as man and wife. After a court-ordered medical exam on April 18, 1889, they went their separate ways, leaving the public to assume the doctor had found Calder to be a woman biologically. Kate married John Barnes Bailey seven years later in 1896.

For a brief period of time after the marriage was dissolved, in May 1889, Baltimore ads touted “The Free Exhibition of the Human Mystery of this Century, Mr. Howard nee Miss Hanna Calder,” at several concert halls around Baltimore until the authorities put a stop to it.

A new life in Florida

Continuing to live as a man in Baltimore, Calder became a bartender, and, on April 2, 1891, married again, this time to Sarah A. Kemp. Sometime between then and 1898, they moved to Highland Springs, Va., where Calder became the proprietor of a successful store named the Farmers’ Exchange. Now using the names Hiram and Howard interchangeably, Calder departed with Sarah for Florida in 1902.

After Hiram Calder’s death in the county home in 1914, the body was laid to rest in an unmarked grave in the “potter’s field” at Michigan Street and Fern Creek Avenue in Orlando, then an unmarked pauper’s burial ground and now known as Orange Hill Cemetery.

Calder had left instructions with friends asking to be buried next to his beloved Sarah, but either his friends were slow to remember or the burial happened too fast for them to intervene. Doris Topliff did take up a collection to have Calder’s body moved, but, sadly, Woodlawn Cemetery in Tampa has no record of Hiram Calder rejoining his wife, and his lifelong fight to be with whom he loved remains unfinished.

This article originally appeared in the Spring 2019 issue of Reflections magazine.