Annie Oakley shot her way out of poverty, overcoming childhood hardships and ultimately earning the respect of royalty, an adoring public, and a great Lakota leader. She was one of America’s earliest superstars, bursting through the gilded glass ceiling of the Victorian era – the main breadwinner during times when it was difficult for women to earn money.

Her appearances in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show in the 1880s and ’90s made her as well known as any famous actress and “probably the most celebrated female performer in the world,” according to writer Larry McMurtry. Her legacy continued in 20th-century popular culture with the Irving Berlin musical Annie Get Your Gun, featuring stars from Ethel Merman to Reba McEntire in the leading role.

Later in life, Oakley would also become a snowbird in Florida, spending winters in Lake County with her husband, Frank Butler, for at least a dozen years. Her longevity as a guest at Leesburg’s Lake View Hotel is now immortalized by a life-sized statue behind the town’s library, not far from where she once spent the winter season. Featured prominently in the sculpture is her beloved companion, Dave the Wonder Dog. She might have spent the rest of her days in the Sunshine State had it not been for dual disasters near the Dixie Highway.

Overcoming the Odds

The woman the world would know as Annie Oakley was born Phoebe Ann Moses (she also used Mosey) in rural Ohio in 1860. She had a traumatic childhood – her father died of pneumonia after getting caught in a blizzard before she was 6 years old. At a young age, she trapped and hunted to help put food on the table for her impoverished family, but it was not enough – she was sent to the Darke County poorhouse. At age 15 she returned to her family and began to hunt small game to sell to the local grocer. Ultimately, she earned enough with her rifle to help her struggling family pay the mortgage.

The grocer who bought game from Oakley encouraged her to enter a shooting competition, and although accounts differ about the exact year and location, they agree that she hit 25 out of 25 targets, defeating her opponent by a single shot. The traveling marksman she bested was an Irishman named Frank Butler, who was much impressed by the young sharpshooter. Butler often included his dog George in shooting performances, and he had George bring Oakley an apple that Butler had shot from the dog’s head, William Tell-style. Presumably, with George’s approval, a courtship between Oakley and Butler ensued.

The couple was married either in 1876 or 1882 – exact dates are unclear, for several reasons. Later in her career, Oakley altered her birthdate to appear younger after a teenage sharpshooter began to steal attention away from her.

It’s also possible that when Oakley and Butler began traveling and performing together, Butler may not have been divorced from his first wife. It is a matter of record, however, that Oakley’s first performance as part of Butler’s act was on May 1, 1882, and that afterward, she adopted the stage name “Annie Oakley.”

Initially, Butler, Oakley, and Butler’s dog George performed on the vaudeville circuit, but in 1884 they signed on with Sells Brothers Circus and toured much of the country. It was during that same year that the famed Lakota leader Sitting Bull bestowed on Oakley the nickname “Little Sure Shot,” because of her shooting prowess and her small stature. The sharpshooter stood just five feet tall and weighed 100 pounds.

The following year Oakley’s career skyrocketed when she joined Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show – her popularity was second only to that of Buffalo Bill Cody himself. She stayed with the show for 16 years and traveled across the globe, entertaining royalty including Queen Victoria and Kaiser Wilhelm. When she left Cody’s show in 1901 after a train wreck in North Carolina injured her back, she was a superstar, known worldwide.

Libel and Leesburg

Oakley and Butler continued to tour and perform after breaking away from Buffalo Bill. Butler had a contract with the Union Metallic Cartridge Company (Remington after 1912) that provided income for the couple.

Like superstars of today, Oakley carefully crafted her public persona and fiercely defended her reputation. In 1903, newspapers owned by William Randolph Hearst falsely claimed Oakley had attempted to steal trousers off a man in order to sell them for money to satisfy a fictitious cocaine addiction. The fastidious Oakley doggedly spent six years pursuing libel lawsuits against many of the newspapers that printed the fabricated article.

The first published account about Oakley in Florida concerns a 1906 trial against the Jacksonville Metropolis newspaper in which she was awarded $2,000 of the $10,000 she requested. She was evidently a force in the courtroom, winning 54 out of 55 lawsuits. Despite her legal successes in defending her good name, however, these courtroom battles were a net loss financially.

In 1908 and 1909, Oakley and Butler appeared in shooting demonstrations for Remington in Gainesville, Ocala, Palatka, Jacksonville, and St. Petersburg. According to a Gainesville Daily Sun newspaper report, the duo began their act by shooting a potato off a stick, one piece at a time, then drilled the ace of hearts with a bullet, and shot through a variety of targets from pennies to marbles in a two-hour demonstration that never had a “dull moment.”

It was around this period that Oakley was invited to Leesburg by a wealthy sportsman from Boston named Nicholas Boyleston. A booklet on Florida tourism raved that Lake County had “excellent tourist accommodations” that would thrill the “sport loving visitor” with opportunities for hunting and fishing.

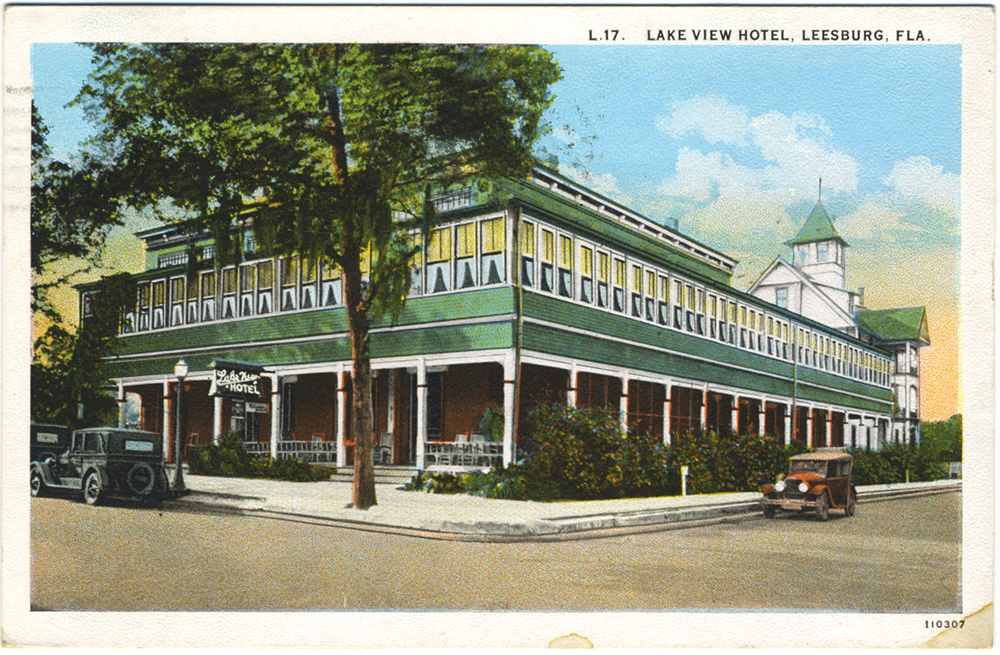

Oakley biographer Glenda Riley writes that Frank Butler loved Leesburg, and that the Lake View Hotel, where the couple made their winter home, was known for catering to sportsmen. Both Oakley and Butler were avid quail hunters, and they found plenty of company for their hunting trips, including Philadelphian John Jacob Stoer, whom Oakley reportedly called the “best quail shot” she had ever known.

In addition to quail hunting around Lake County, Oakley was also said to have shot and skinned a 7-foot-long rattlesnake, stalked black bears in the Ocala National Forest, and performed shooting exhibitions for tourists. For more than a decade, the Butlers enjoyed wintering in Lake County, but two tragic events would darken their perception of the Sunshine State.

Trouble on the Dixie Highway

On Nov. 9, 1922, the Butlers and their fellow snowbirds, the quail hunter Stoer and his wife, Margaretta, were speeding toward Leesburg in a chauffeur-driven convertible on the Dixie Highway about 50 miles from Daytona Beach. There are multiple accounts of what happened next, but the results were conclusive – the car “turned turtle,” as one eyewitness recalled, rolling over and pinning tiny Annie Oakley underneath.

Once extricated, the world’s most famous sharpshooter was rushed to Dr. Bohannon’s Hospital and Sanitarium, a facility that catered to the health-care needs of tourists. Chief surgeon Clyde C. Bohannon found that Oakley, now 62 years old, had broken her hip and her ankle, and after surgery, she endured a long period of rehabilitation.

Butler booked a room across from the hospital, and Oakley’s half-sister came down to help during her

convalescence, which kept her under Dr. Bohannon’s care for six weeks.

When she was finally able to return to Leesburg, Oakley expressed her gratitude to the well-wishers who had sent her more than 2,000 letters and telegrams. In a note published in American Field magazine, she expressed her appreciation for all her friends had done for her and said she expected to recover fully in time.

Privately, however, doctors expressed doubt that she would ever shoot again. The woman who had once effortlessly picked off targets while standing on the back of a horse now had her mobility constrained by a leg brace that she wore the rest of her life.

The Death of the Wonder Dog

Oakley and Butler never had children, but they were devoted to their dogs, including their much-celebrated black-and-white English setter, Dave. Like Butler’s poodle George, Dave was part of their act – a widely reproduced photo shows the dog sitting obediently while Oakley aims at an apple resting on his head during a segment of their routine, just as Butler had done years earlier with George.

During World War I, Dave the Wonder Dog earned another moniker – the “Red Cross Dog.” During performances with Oakley, Dave successfully “sniffed out” cash donations that were hidden in handkerchiefs in the audience. Dave raised more than $1,600 for the cause, and his fame grew so much that he was “scarcely less known than his mistress,” according to one report.

Three and a half months after the auto accident, Oakley was still recuperating in Leesburg when tragedy struck again. A passing car hit Dave on Main Street in front of the Lake View, and he died on Feb. 25, 1923.

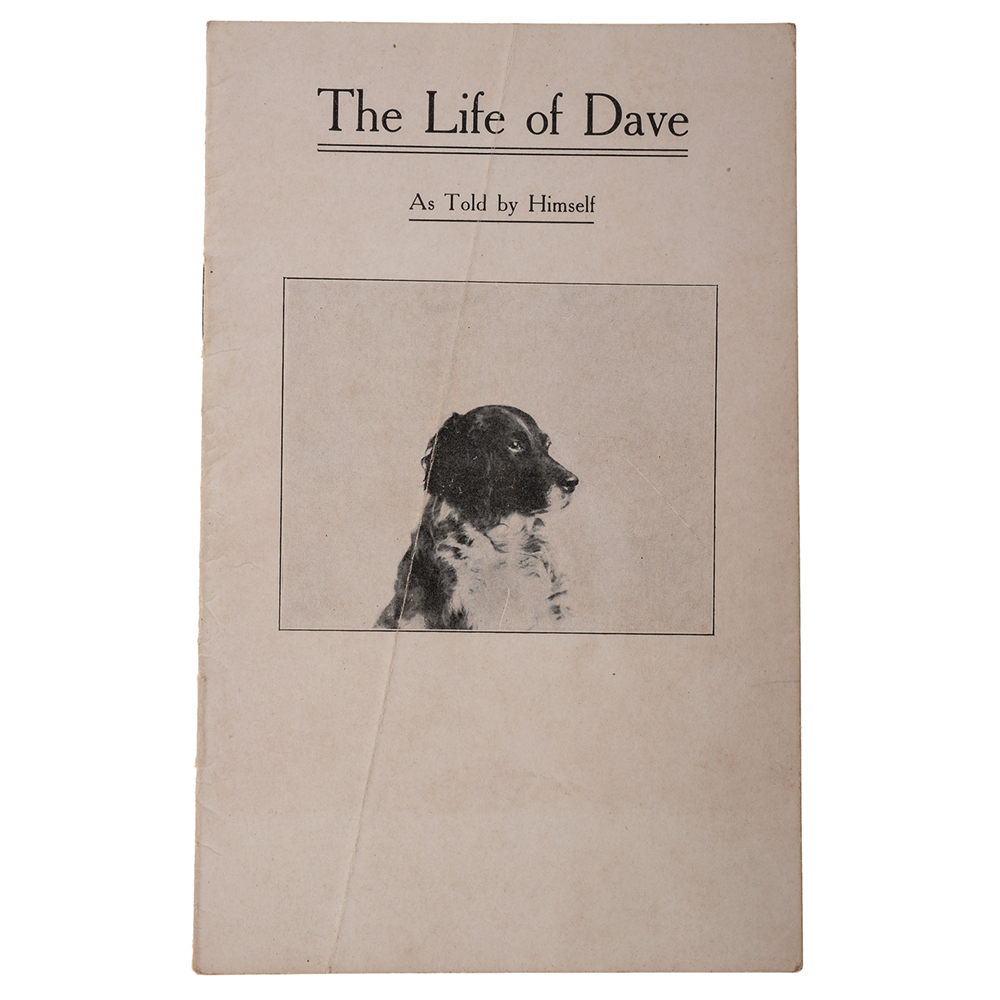

The grieving couple felt the pain of Dave’s death as “parents would feel the loss of a child,” one newspaper noted. To pay homage to their canine companion, Butler penned a short booklet titled “The Life of Dave as Told by Himself.”

“Dave was more than some humans,” Butler wrote on the back page of the booklet. “He sat for weeks watching faithfully by the bedside of his mistress and would snuggle close, tapping gently with his little paw, his big eyes burning with love.” Dave “awaits us both in the Happy Hunting Ground,” Butler concluded.

The Butlers wished to bury their cherished pet in the city’s Lone Oak Cemetery, but were rebuked by officials who said only people could be interned there. There is some debate as to where Dave’s final resting place was, but most accounts suggest it was on property owned by George and Annie Winter, friends of the Butlers.

Leesburg lore maintains that Oakley was so irritated at the city for the slight that she left, never to return. Other accounts claim just the opposite – that over the next few years, the Butlers rarely left Leesburg.

A letter from Butler to Oakley’s niece in 1925, however, shows that he was beginning to sour on the Lake View Hotel and Leesburg, writing “the fishing is not good here and the hotel is rotten.”

Oakley’s Final Hurrah

Annie Oakley had overcome adversity her whole life, so it only seems natural that she would defy the doctor’s expectations about being able to perform again. A month after Dave’s demise, she and Frank appeared before a Philadelphia Phillies spring training game at Leesburg’s Cooke Field, where the Phillies trained from 1922 to 1924.

With players and fans watching from the wooden bleachers, Oakley balanced on one leg and shot at pennies tossed into the air, hitting a dozen without a miss. After she blasted five eggs that Butler tossed into the air while she shot left-handed, the Phillies “broke into applause,” claims Oakley biographer Riley. For a time, Little Sure Shot was back.

At the end of 1924, Oakley and Butler returned to Ohio, eventually ending up in Darke County, where she had spent her childhood. Oakley got her affairs in order before succumbing to pernicious anemia on Nov. 23, 1926. Her partner of fifty years, Frank Butler, followed her to the “Happy Hunting Grounds” just three weeks later.

In a thoughtful article, Tallahassee scholar Claude R. Flory noted that although Oakley’s name conjures up notions of the Wild West, she was really an Ohio girl whose reputation was made through performances as far away as England and France. Like so many Midwesterners, though, she long wintered in Florida, and despite her fascinating, globe-trotting personal history, two of the most “pivotal events of her life” happened in the Sunshine State. She was a part of our history, as Florida was of her’s.

Article by Rick Kilby from Reflections magazine, Fall 2019.