By Jim Robison from the Winter 2013 edition of Reflections Magazine

Whether you’ve served in the U.S. Army or not, a lot of folks have heard the Army’s “HOOah” cry, especially after Al Pacino’s character popularized it in the movie “Scent of a Woman.” But most folks, even most Floridians, have no idea that the cry has roots in our state and to Seminole history.

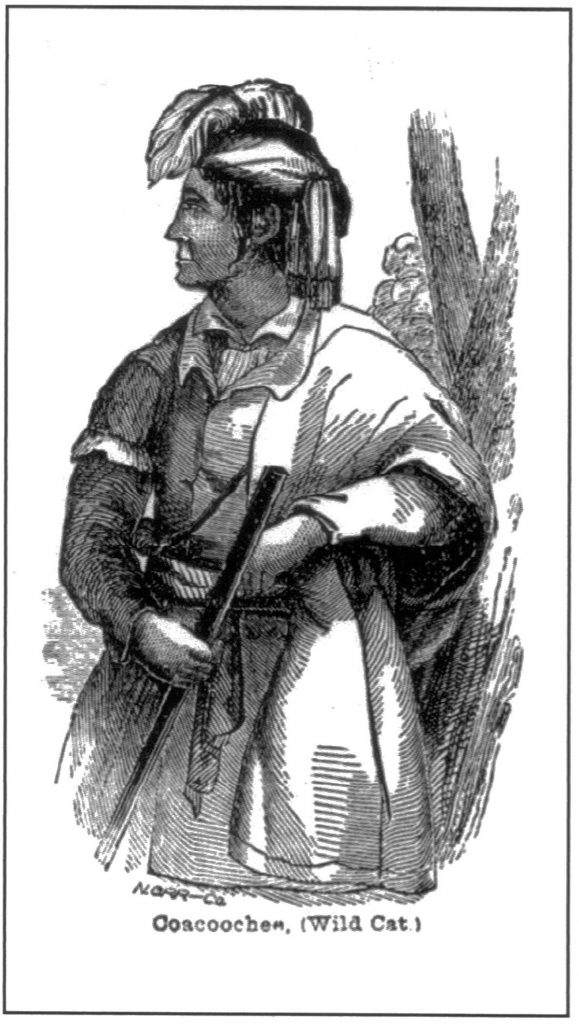

The catch-all response for just about any military situation shouted by grunts to top brass can be traced back to Coacoochee, the Seminole whose name means “chief-to-be.” (His father was King Philip, an important Seminole chief.) The 2nd Dragoons at Fort Mellon (Sanford) nicknamed him Wildcat.

The same soldiers told lore passed down by military generations that found its way to Hollywood when Pacino’s Lt. Col. Frank Slade, the bitter, blind retired Army officer in the movie, repeatedly roars, “HOOah!”

Army Spc. James Pernol, a military public affairs journalist at Fort Dix, N.J., cites the official Army position, supported by military history, that attributes the origin of the term to Coacoochee and the 2nd Dragoons (mounted riflemen) assigned to the Florida wars in 1841.

At a banquet following truce talks with the Seminoles, Coacoochee listened as officers of the garrison offered toasts, including “Here’s to luck!” and “The old grudge” before drinking, according to many military sources. Coacoochee turned to the interpreter Gopher John, who explained the toasting. Coacoochee is said to have raised his cup high and shouted, “Hough!” The 2nd Dragoons joined in, creating the enduring legacy.

Coacoochee turned out to be a major impediment to the Army’s goal of ridding Florida of the Seminoles and forcing them to reservations west of the Mississippi River. He led the Feb. 8, 1837, attack on Camp Monroe, renamed days later for Capt. Charles Mellon, the Army’s only fatality. The settlement that grew up around the fort became Mellonville, one of the first county seats for Orange County, which until 1913 included all of Seminole County.

Captured and put in prison at St. Augustine, Coacoochee escaped from the Castillo de San Marcos and slipped into the pine forest of the St. Johns River to freedom. Historians say his escape to rally Seminoles to continue resisting extended the Second Seminole War by four years.

Coachoochee frustrated the Army, leading ambushes and evading soldiers by disappearing into the swamps. He took part in the battle of Okeechobee on Christmas Day 1837 and other skirmishes. Zachary Taylor outraged the nation by bringing in Cuban-bred bloodhounds to track the Seminoles.

On March 5, 1841, Coacoochee delivered an eloquent statement to Walker Armistead, then commander of the Army in Florida. “I have said I am the enemy to the white man,” he said. “I could live in peace with them, but they first steal our cattle and horses, cheat us, and take our lands. The white men are as thick as the leaves in the hammock; they come upon us thicker every year. They may shoot us, drive our women and children night and day; they may chain our hands and feet, but the red man’s heart will be always free.”

Historian John Mahon writes that the name Wildcat was bestowed because Coacoochee was famed for his valor and leadership in battle. In doing so, he won the respect of his enemy.

Dragoon footnote: The late Florida historian and retired Army sergeant-major Charlie Carlson, author of “Weird Florida,” confirmed that Army armored cavalry units trace their heritage to the 2nd Dragoons. Christine Kinlaw-Best’s “The History of Fort Mellon” and Carlson’s “From Fort Mellon to Baghdad, A Timeline Evolution of the 2nd Dragoons,” trace today’s 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, among the Army forces sent to fight in Iraq, to the Florida dragoons, making the regiment the oldest continually serving cavalry unit in the Army.

Dragoon footnote: The late Florida historian and retired Army sergeant-major Charlie Carlson, author of “Weird Florida,” confirmed that Army armored cavalry units trace their heritage to the 2nd Dragoons. Christine Kinlaw-Best’s “The History of Fort Mellon” and Carlson’s “From Fort Mellon to Baghdad, A Timeline Evolution of the 2nd Dragoons,” trace today’s 2nd Armored Cavalry Regiment, among the Army forces sent to fight in Iraq, to the Florida dragoons, making the regiment the oldest continually serving cavalry unit in the Army.

Jim Robison is the author of many books about Central Florida’s past, including “Seminole County’s Centennial: Celebrating a Century of Success.”