2,000 ounces of common sense

2,000 ounces of common sense

By Melissa Procko

Channel 9 aired their 680th editorial on December 19, 1963. Titled “Human Nature,” the editorial closed with a quote Joseph Brechner hoped to be remembered by: “One ounce of common sense in race relations is worth a thousand rulings from every court in the land.”

In the 1941 Mayflower Decision, the Federal Communications Commission declared that radio broadcasters were not permitted to editorialize, concluding that “the broadcaster cannot be an advocate.” The commission reversed their stance in 1949, permitting broadcasters to share their opinions as long as they also aired opposing views. Many broadcasters struggled to navigate this new freedom, walking a fine line of expressing their partisan views without presenting their stations as anything other than neutral.

This article contains various Channel 9 editorial excerpts from 1960 to 1969, which can be found in the Joseph L. Brechner Collection at the Orange County Regional History Center.

By the time Joseph Brechner moved to Orlando in 1953, he was well versed in expressing his editorial voice. Joseph and his wife, Marion Brechner, teamed up with John Kluge to create the WGAY-AM-FM radio station in Silver Spring, Maryland, following their military service during World War II. Through his work for WGAY radio, Brechner refined his craft of serving as a voice for the community.

In 1953, Brechner and Kluge sold their radio station and used the money to purchase WLOF Radio in Orlando. The two moved to Central Florida and, with WLOF vice president and general manager Donn Colee, soon formed the Mid-Florida Television Corporation with the goal of obtaining a television license.

Mid-Florida Television Corporation was granted a 90-day operating permit by the FCC and in 1958 WLOF-TV (later WFTV) became Orlando’s second television station, and only ABC affiliate, in Central Florida. By 1960, Kluge and Colee had left WLOF for stations in Washington, D.C.

Now in charge of daily operations, Brechner brought his personal beliefs to the news department, and the station broadcast their first editorial on October 6, 1960.

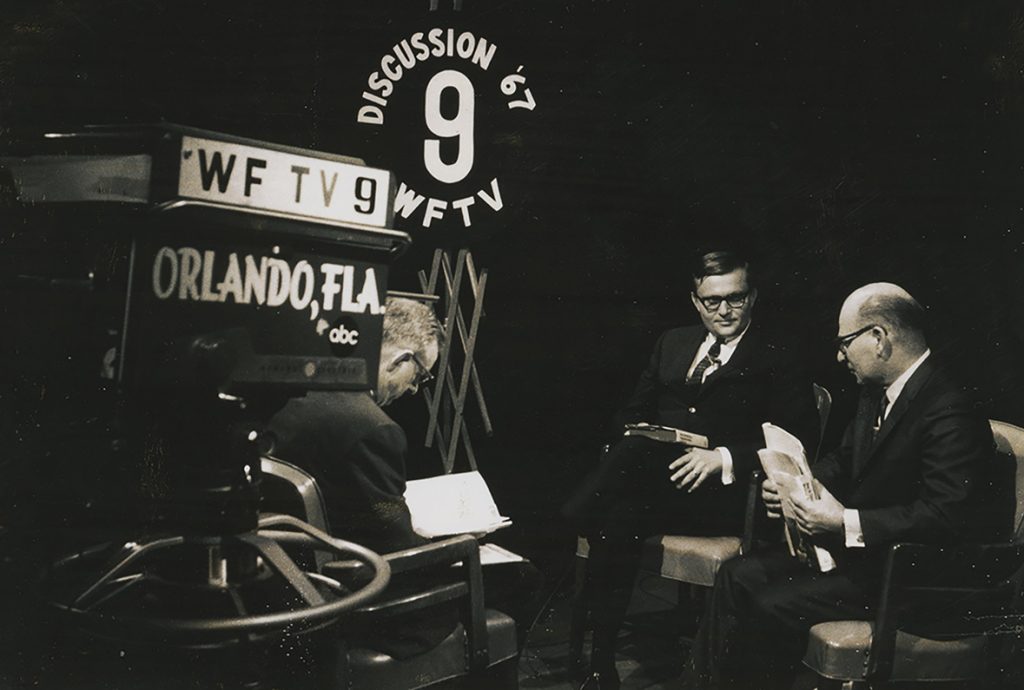

The station’s editorials, mostly written by Brechner himself and read on-air by news director Ray Ruester, often brought controversial topics to Orlando’s living rooms. Issues ranged from voting and patriotism to the need for higher education in Central Florida, but Brechner most commonly circled back to the subject of civil rights.

As a Jewish man, Brechner was no stranger to discrimination. His experiences made him keenly aware of what others might be facing, and his platform provided him an opportunity to speak up. Brechner’s attitude on how Orlando might approach the matter can possibly be summed up in one quote from the editorial “Common Sense in Race Relations” broadcast on November 30, 1960: “Closing our eyes will not make the problem disappear.”

Brechner firmly believed that in order to address racial issues, they needed to be accurately reported on and publicly discussed. He served on Mayor Robert Carr’s Interracial Advisory Committee, working with black and white community leaders toward peaceful desegregation solutions. The station’s editorials frequently reported on the activities of the advisory committee, keeping the citizens of Orlando informed about the process of integration in their community.

Brechner was not afraid to call out other news outlets for inaccurate coverage, and he certainly did not mince words in his blunt commentary about hate groups. “Beware the prophets of violence and intolerance,” his editorials warned viewers. “They would destroy Americans and America.”

His strong editorial opinions were met with mixed reviews. Some editorials were solely devoted to reading letters from viewers ranging from compliments to criticism. One viewer called the station “completely irresponsible” in reply to an editorial about race relations in Central Florida. Another wrote admirably, “Your stand against extremism in any form, be it to the right or left, is very proper and very American … deserving the full and overwhelming support of the community.”

Despite intimidation attempts from the Ku Klux Klan — in the form of stickers left on the doors of the station reading, “A Ku Klux Klansman was here,” or threats of violence specifically directed toward employees of the station — Brechner never backed down. Even when a viewer wrote that they were concerned the station was covering “more dangerous subjects,” Brechner made his and the station’s stance clear: “We need more public thought and discussion on the more dangerous subjects … Out of controversy comes light.”

Brechner was forced to relinquish control of WFTV in 1969 due to FCC hearings regarding competition for the station’s operating license. In 1981, the five companies competing for the station’s license entered a joint-operating agreement, and Mid-Florida Television held 28.3 percent ownership of Channel 9 until the station was purchased in 1984.

During Brechner’s time as president, Channel 9 was anything but segregated. He facilitated open discussion of difficult issues through his editorial policy, special programming, and moderated panels. When topics of race were being addressed in an open forum, black and white community leaders were present to express their voices. WLOF hired the first African American disc jockey in Florida under his leadership. Brechner used his platform to openly campaign for civil rights, pushing for better employment and on-the-job training, improved living conditions, and equal opportunities across the board.

WFTV broadcast their final editorial, number 2,000, on March 31, 1969, titled “Until We Meet Again.” Over the course of nine years, Joseph Brechner tackled difficult issues such as racism and extremism in a way no one in Central Florida had ever done before. His editorials pushed Orlando’s problems to center stage and convinced people to start listening. 2,000 discussions started and thoughts shared. 2,000 chances to understand an opposing view. 2,000 ounces of common sense so desperately needed in a time when being an advocate on the air was incredibly rare.