Russell’s Pavilion, the Mystery Sink, and the Fairview Geyser

By Tracy Hadlett from the Fall 2015 issue of Reflections from Central Florida, the Quarterly Magazine of the Historical Society of Central Florida, Inc.

College Park’s history of water-themed attractions include Orlando’s very first water park, a mysterious sinkhole, and a spouting well. The Orlando neighborhood today known as College Park was originally home to citrus and pineapple growers. The Great Freeze of 1894 and 1895 stalled development there and all over Central Florida, but by the early 20th century, settlement in the area bounced back.

Keeping cool at Joyland

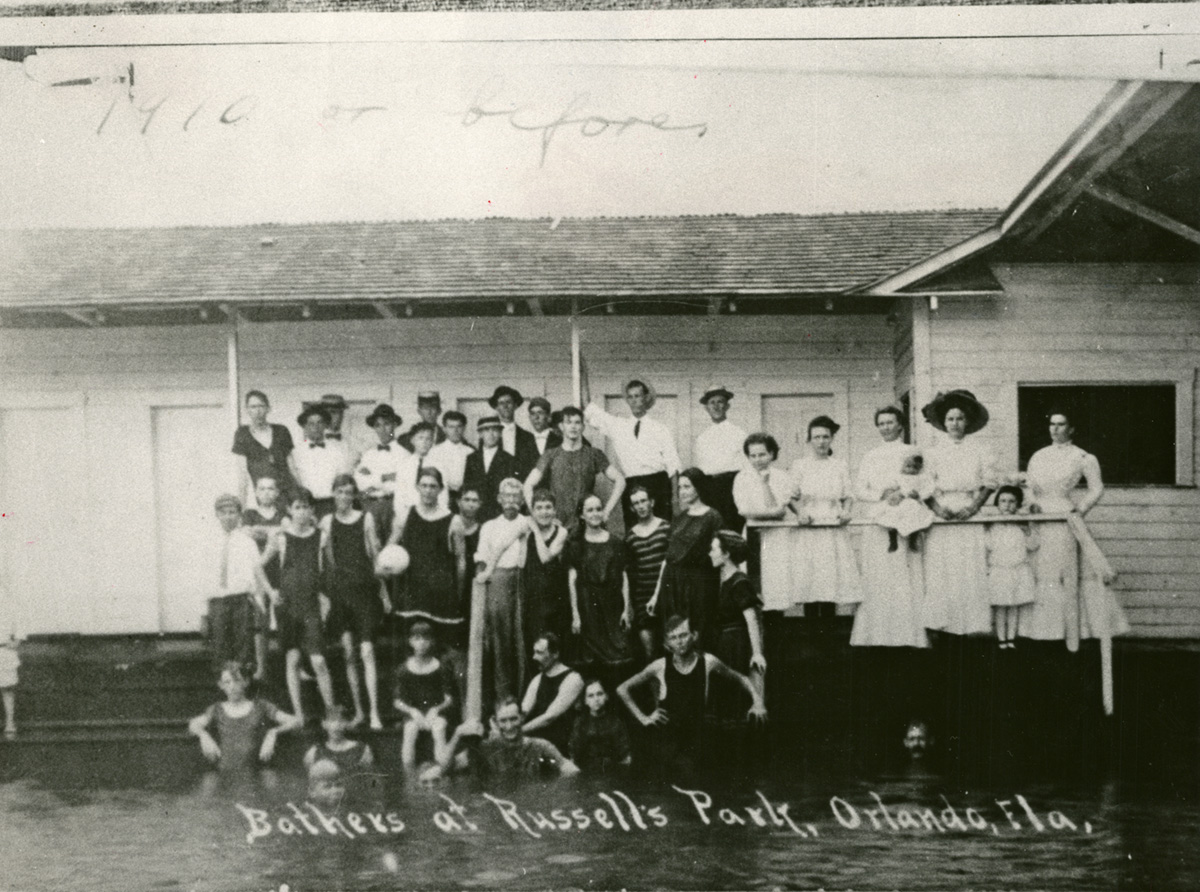

In 1910, George Russell built an entertainment destination for Orlandoans on Lake Ivanhoe and called it Russell’s Point – the first water park in Orlando. It was later renamed Joyland, thanks to a contest to find a more fitting name for the park, which featured swimming, waterslides, a pavilion, a dance hall, dressing rooms, a concession stand, and a picnic area. There was also a dock with 50 boats for gliding and fishing on the lake. People flocked to Lake Ivanhoe to cool off and have fun. After nine years in business, Joyland was sold to the Cooper-Atha-Barr Company, which developed nearby land into the College Park subdivision.

A deep mystery

The Mystery Sink, also known as Emerald Sink, is a water-filled sinkhole located on the northern edge of Orlando’s College Park neighborhood. A 1939 newspaper ad suggests that the sinkhole might once have been promoted as a roadside attraction called “Nature’s Mystery.” Today, the sinkhole is on private property, surrounded by a tall fence, and is inaccessible to the public. The surface is roughly 150 feet in diameter, and the profile has an hourglass shape. The appropriately named Mystery Sink has been estimated to be as much as 500 feet deep, but no one really knows for sure.

Sinkholes are a naturally occurring feature of the Florida landscape, according to the state’s Department of Environmental Protection. They may be caused by low levels of groundwater or by surface water eroding the limestone bedrock. Mystery Sink formed through erosion and collapsed deeply enough to connect it to the underground aquifer.

In August 1970, two scuba divers, Hal Watts, 31, and Fred Schmidt, 16, dove the Mystery Sink in search of a lost safety vest. Everything was going as planned until Watts realized that his diving companion was no longer near him. Watts spotted Schmidt’s light below him, but it disappeared before he could reach it. Watts blacked out during his search. He regained consciousness, but was unable to locate the teen. Two separate attempts were made to find Fred Schmidt’s body, both unsuccessful. The first attempt failed due to the excessive depth, and a second attempt resulted in the death of diver Bud Sims. The sinkhole has been closed to the public ever since.

Lake Fairview’s spouting well

Not far from the Mystery Sink, Lake Fairview once had its own mystery that brought visitors to gawk at what they thought was a natural wonder. The Lake Fairview “spouting well” first appeared in the early years of the 20th century at the Davis-McNeill farm on the lake’s south side, where a geyser began to erupt about every six minutes and reached heights of 75 to 100 feet.

According to a short article in Scientific American magazine in 1911, Orlando officials had faced problems because the city’s lakes often overflowed – an especially irksome problem for truck farmers near Lake Fairview, who found their fields flooded.

The remedy was to drive pipes hundreds of feet into the ground in search of underground passageways into which to drain the excess water. At Lake Fairview, the top of one such pipe near the lake’s edge sat only 5 inches below the water’s surface. The so-called geyser resulted when air pressure built up in a natural underground chamber, reached a critical point, and rushed up out of the pipe, the article suggested. Soon farm manager R.D. Eunice asked spectators for a small admission fee; those who didn’t want to pay just stationed themselves across the lake to watch from a distance, waiting through the interval between spouts. The pipe was capped in the 1930s, and Orlando’s spouting well was no more.